The science of love

Can we keep the rose-colored glasses?

You finally matched with someone cute online. But then the next question pops up: what are you going to say first? What are they going to say? It’s a delicate game to play, and easily overthought.

A couple weeks later and it’s the first date. Friends help you get ready, maybe you hold hands for the first time. Or more.

It’s your first anniversary, but it’s less overwhelming than the first date. You know this person. All the giddiness has faded, love and trust are left in its place.

In these scenarios, it’s easy to focus on the feelings: excitement, anxiety, love. But there’s a reason for each of those feelings, and it’s not just because you’ve got a hot date. It’s because of the chemicals in your brain and the experiences you have.

A racing mind

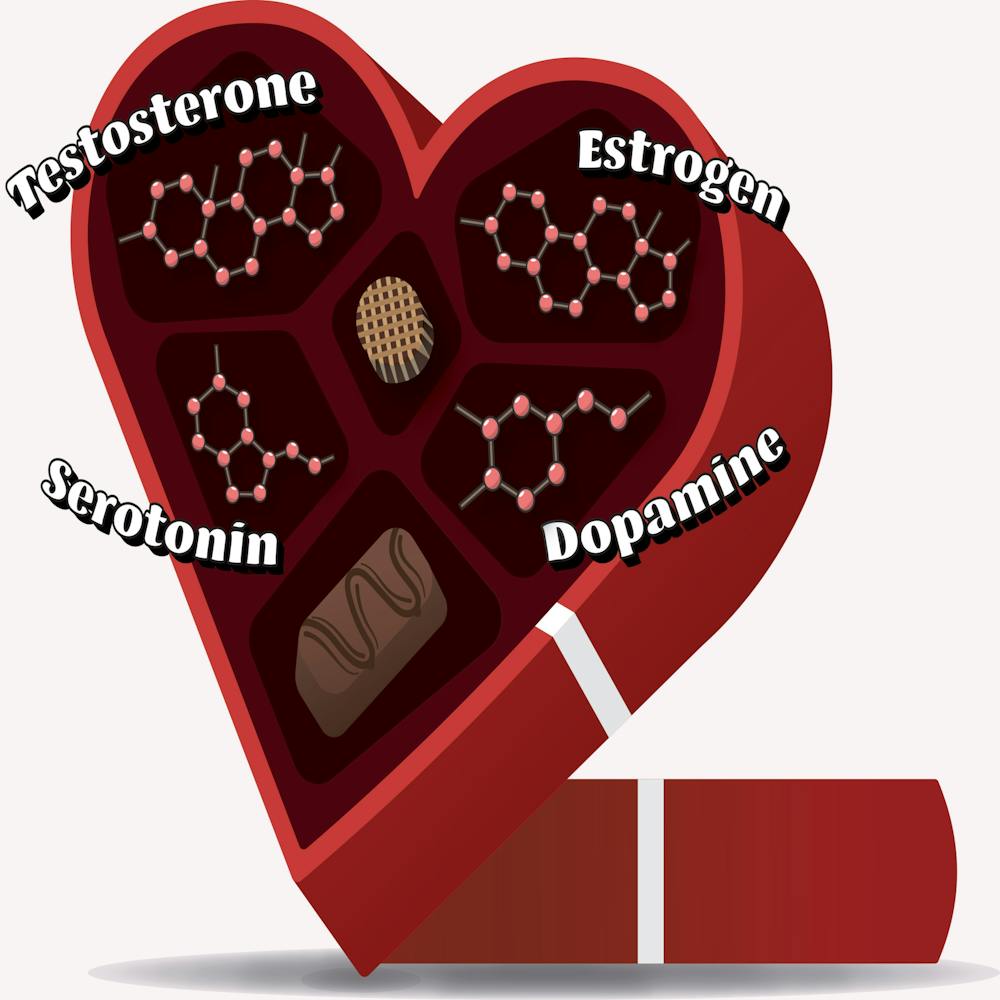

Dopamine, oxytocin and serotonin are three main chemicals that are activated in these situations, according to Yannick Marchalant, an associate professor of neuroscience who has been at Central Michigan University for 10 years.

“We have a few structures in the brain that are emotionally oriented,” he said, and referenced the amygdala (related to strong emotions) and hippocampus (connected to memory).

The amygdala and hippocampus are both part of the limbic system, a network of structures that, according to the Cleveland Clinic, help regulate a person’s emotions and behavior.

“In terms of things we like, we have another system that is mostly located at the base of the brain called the ventral tegmental area (VTA)… and it’s linked to another structure,” Marchalant said. “That connection is mostly dopamine, and that is the place that gets activated when we do things we like.

“When you like someone, you’re going to activate that part (of your brain).”

That dopamine hit also connects to the frontal cortex, the part of the brain where Marchalant said rational decision-making happens (or tries to).

“Our brain has that balance that sometimes gets… left off when love or the sensations of something you really enjoy doing takes over,” he said. So the VTA can make you want to spend more time with someone you like, but Marchalant said it also “tempers with our capacity to make purely rational decisions."

That’s also why it can be difficult to accept criticisms about people we love.

Oxytocin has a significant role in both male and female reproductive systems each step of the way, from relationships, to sex and through the birth process, according to Health Direct.

Marchalant said a prime example of oxytocin presence is the bond between mother and newborn, but it’s also part of the equation for enjoyable sex.

Serotonin levels can change over the course of a relationship, too. This hormone also acts as a neurotransmitter, carrying messages from the brain to the rest of the body, according to the Cleveland Clinic.

Essentially, Marchalant said, happier people have more serotonin. But at the beginning of a relationship, serotonin levels are actually lower, having an inverse relationship with stress.

“(The) love process seems to trigger a little bit of anxiety in us, a little bit of stress,” he said. "This is generally linked to the uncertainty a new relationship brings, prompting questions like ‘Why is he not texting me very fast? Why is he not responding?’

“Love is driving you to do things, and it’s a positive in your brain, but it can… also cause a little bit of stress,” he said. That can go away over time as the relationship becomes more secure.

With all of this in mind, does seeing “behind the curtain” of our brain chemistry make a person less susceptible to the ups and downs of relationships and the emotions that come with it? Marchalant said no.

“I think we’re really good at ignoring how the brain works when you’re subjected to things,” he said. “It doesn’t make you a more rational person when you have knowledge about those things.”

We can still be triggered by emotions, but he said having an inside understanding of how it works can make it easier to look back and reflect.

The social scenario

But brain chemicals aren't the only driving factors. If you ask Amanda Garrison, a faculty member in the sociology department at CMU, we're also influenced by our perceptions of love.

Garrison said that the way we understand love and romance is heavily influenced by everyday factors like watching our parents and the media we consume.

“It’s in the way we see relationships; it’s the way that we see movies and media; it’s the way government policies are written," she said.

"Babies come out with hardly any neuroreceptors at all, but within like 18 months, it’s like a jungle in here," she said. "Romantic love begins as soon as there are representations of family, marriage. It's like the coming together or commingling of things that have nothing to do with love."

Garrison gave the example of the movie "The Breakfast Club" from 1985. From watching that movie, the viewer is seeing monogamous, heteronormative love.

“If I get to be in detention in high school, I’m gonna meet a really cute boy," she said, and laughed. "It’s not like that at all. It’s a classroom where there’s a teacher reading a book and a bunch of people I don’t know… there’s nothing romantic about that."

But all of those movie moments leave out the boring stuff in between, Garrison said.

"We get to see these moments that are speckled throughout our media lives and our friendships and things like that, that create a sense of what a relationship is supposed to be without the reality of the struggle, of the work that is related to that," she said. "Love isn't work, but relationships are.

"It's like history. When you think about history... the moments we read are remarkable. What we don't get to read about is all the boring (stuff) in between the things that happened. Relationships are like that, real relationships are like that."

Monogamy can also be a structure affecting our relationships, Garrison said. It can lead to a mindset that envisions a "perfect one" for you, when really, there are plenty of people an individual could be compatible with.

"Monogamy also tends to create in some of us this feeling that... every single one could be 'the one,' instead of just anyone," she said. "You have that gut feeling 'I just knew it, it was love at first sight,' until you break up, and the story changes."

The moral of the story, she explained, is that relationships have the meaning that we give them. And that doesn't just apply to romantic relationships, but familial and platonic.

“To some extent, asking to differentiate between types of love suggests that there would be different components to the chemical oxytocin that would help us differentiate between them," Garrison said. "So the differentiation has to come from the meaning that we make."