'There's hope for those who experience this:' A sexual assault survivor's 35-year journey to healing

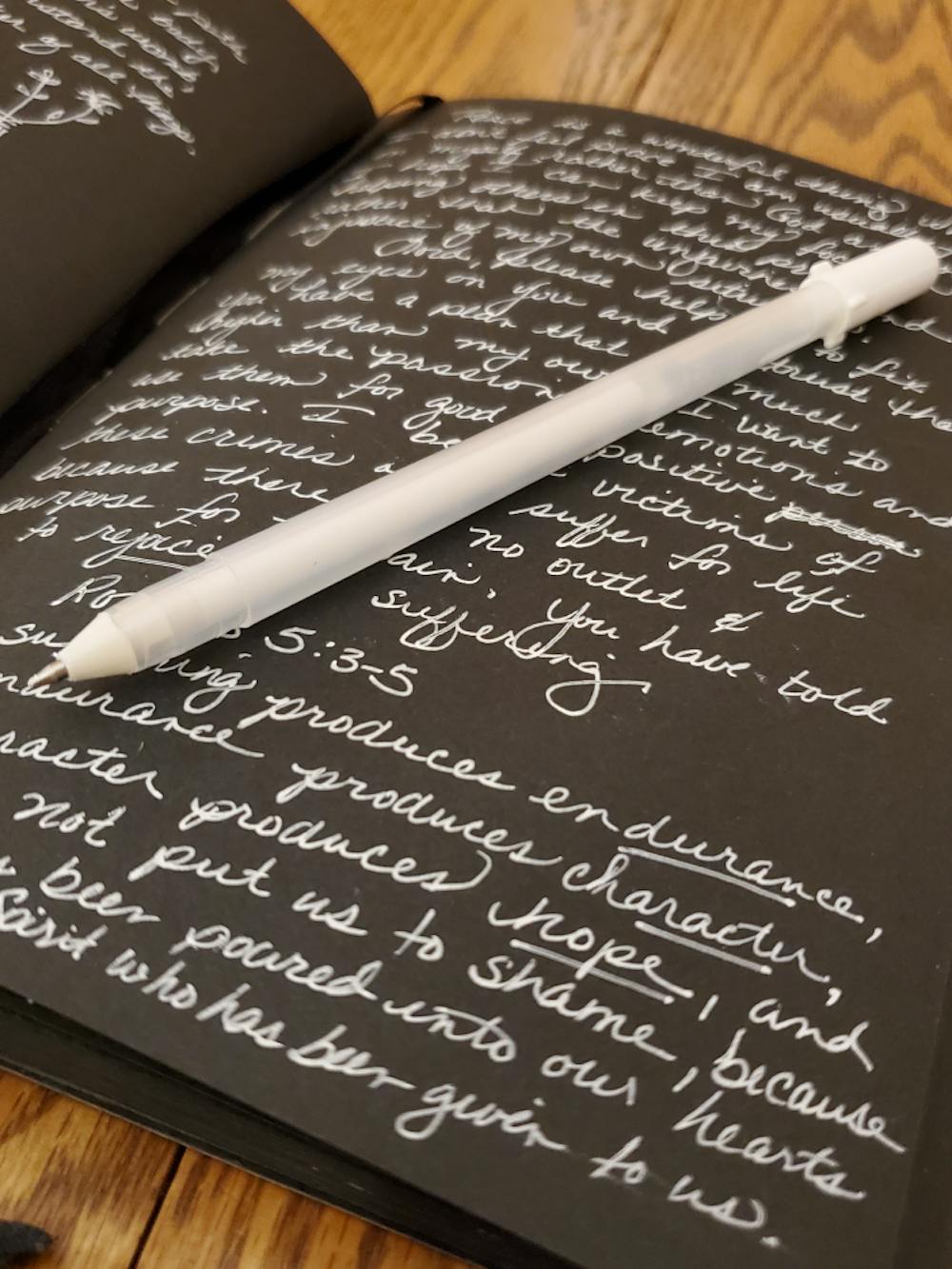

The black paged journal and white pen that Lisa Saruga used to write her story. Courtesy Photo | Lisa Saruga

Editor's Note: Lisa Saruga's rapist has never been arrested. She still considers him a threat to her and her family. She writes and speaks about her sexual assault under a pen name for her safety.

As she walked through Barnes Hall this May, Lisa Saruga peered into rooms and thought about the memories she created there. The Central Michigan University residence hall she lived in for two years was about to be torn down.

She stood in the lobby and remembered trying to stay awake during her overnight shift at the front desk. Walking by, she peered into the student lounge and recalled the time she and her floor-mates gathered there to watch the world premiere of Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” music video.

As she relived those happy memories from 35 years ago, she couldn’t help but feel like they were being overshadowed by the trauma she experienced in Barnes.

After 35 years, Room 205, the place where she was held at knife-point and sexually assaulted, looked mostly the same.

Standing in the white cinder block room, Saruga became overwhelmed with emotion. Her husband approached her with some Sharpie markers.

“Write until you run out of ink,” he said before he left the room.

She sat in the corner and wrote on the walls, starting with her assailant's name. Then she wrote down her thoughts and feelings as they poured out of her – on the wall that she banged her fists on, more than three decades ago, while crying for help as she was being assaulted. She also covered the wall in scripture about forgiveness. Nobody is too far-gone for God to reach, she reminded herself.

Then, her longtime friend handed her a sledgehammer.

“Where do you want to start?” he asked.

Swinging the sledgehammer, she connected on the spot where she had written the man's name. Saruga broke through the first layer of plaster, then her husband and friend took turns demolishing the wall and the pain it represented. Finally, they broke through the wall and into the next room.

Saruga looked through the hole in the wall and thought about how far she has come since the early morning hours of Oct. 15, 1983.

“I made a couple of small dents in 1983," she said, "but this year was a lot of hard work."

The attack

A man in a ski mask used a razor blade to cut through a screen in the basement of Barnes Hall in the early hours of Oct. 15, 1983. Saruga was sleeping in her dorm room.

The man woke her up. He had a knife in his hand. He told her he wouldn’t hurt her as long as she did what he said. He forced her to perform oral sex on him twice. When she didn’t cooperate, he cut her legs with the knife. During the attack, she banged on the wall, screaming for help. She attempted to gouge his eyes to try to stop him.

She also prayed. She prayed out loud, both for herself and for the man attacking her.

“You go to sleep now,” he said to her after the attack. He stood outside her door, waiting for her to fall asleep. Every few minutes, he peeked into the room to see if she was awake. She felt like a hostage.

After he left, she got out of bed, locked the door, and called her boyfriend. He and his friend immediately came over and took her to the Residence Hall Director to report the sexual assault. She was taken to the hospital for an examination.

After returning to Barnes, she took a shower in the floor's the community bathroom. Nobody was on her floor – her RHD had called a floor meeting after her attack. Leaving the bathroom, and realizing that she was alone, was the first time she was confronted by the reality of what had happened to her.

“I remember being really scared because if I scream, nobody would hear me,” she said describing a feeling of vulnerability immediately after the attack.

Suddenly, a large group of people came up the stairwell. It was clear to them that she was the one who had been attacked. Though she had just been through the most traumatic event of her life, Saruga believed she could will herself back to normality. She was urged to go home and take some time to heal herself, but she refused. She attended two counseling sessions, but insisted she was fine.

“I was attacked on a Saturday morning and I was back in class on Monday,” Saruga said. “I just kind of stuffed it (inside) and stopped talking about it. (But) I had to be emotional enough with the police so they would believe me.

"It was paralyzing, really.”

On the Monday after her assault, Central Michigan Life published a short, front page story about her rape. She said the article created a lot of buzz on campus. Saruga heard classmates talking about her assault, but they didn't know it was her.

"I remember going to class," Saruga said, "and hearing people talk about how stupid (the woman who was assaulted) was for leaving her door unlocked."

Moving on

After graduating from Central Michigan University, Saruga attended Bowling Green State University, where she received two master’s degrees: one in higher education administration and another in counseling. She returned to CMU to serve as a residence hall director.

She still visits campus frequently, mostly to visit with friends who are working there.

“I never broke my connection with CMU,” she said.

Saruga describes her life as happy and fulfilling. When her children started school, Saruga began working as a guidance counselor. She also has worked in various public schools and universities. She volunteered at her local hospital as a victim advocate. Most recently, she served as a director of worship ministries at the church in her hometown.

One phone call in June 2018 turned her life upside down.

CMU Police Det. Jason VanConant called her and requested a meeting, but didn’t explain what it was about. Saruga called a friend, who is a CMU administrator, to find out more.

Her case was being reopened.

When she met with the detective, Saruga was surprised that there was new information after 35 years. She told VanConant that her attack changed her life forever. He told her after more than 30 years, police had a suspect in her assault.

VanConant asked if she wanted to pursue the investigation. Saruga told him she wanted to move forward because she believed there may be other victims.

She also wanted closure. And justice.

She would get neither.

Guilty conscience

Thirty years ago, two friends from high school got together for a visit. One had just left the military, the other had graduated from CMU. Sometime during the visit the man told his friend a story about a rape he committed a few years earlier while at CMU. He described how he entered a woman’s room, wearing a ski mask to conceal his face. He explained how he threw her to the floor and held a knife to her throat. He said he raped her.

The friend couldn't decide if the former CMU student was confessing or exaggerating an experience he had on campus. He did decide to end the friendship. He also decided not to report the conversation to police.

In 2018, he changed his mind.

That happened after he spoke to another friend to see if he had heard the same rape story. When they determined they had heard the same story, the ex-military man called CMUPD. According to the police report, he explained that he felt guilty for holding onto this information for 30 years.

CMUPD began investigating Saruga's case almost immediately. She reported her assault to police the day it happened. However, the investigation was handled very differently in 1983 compared to 2018.

When Saruga spoke to police the day of her attack, she said she felt like she was trying to prove her innocence. She said the detective at the time asked if she watched a lot of TV and movies because what she reported was not a typical sexual assault.

“They didn’t know as much about how to work with victims back then,” she said. “I definitely experienced disbelief.”

She said the detectives also didn’t believe her when she said she was a virgin.

During the investigation, police collected six pieces of evidence: Saruga’s clothing, her comforter and her sexual assault evidence collection kit. After the investigation was closed, the department burned the clothing. It is unknown what happened to the comforter and the rape kit. There is no proof that police sent the kit to the Michigan State Police Crime Lab. VanConant also tried to obtain her medical records, but McLaren Central Michigan Hospital holds onto records for 25 years and then destroys them.

One of Saruga’s neighbors in Barnes saw the man that night and remembered enough for the police to create a composite drawing.

“The drawing was never sent to the newspaper, it was never posted in town,” she said. “It just got put in a file.”

Saruga noticed a significant difference in tone between the first investigation and the second.

“It was a very different experience,” she said. “I felt like they were on my side.”

After introducing himself, the first thing VanConant said to Saruga was, “I want to apologize for what happened back then. I want you to know I believe every word you say.”

Saruga felt like she was well-taken-care-of during the second investigation. VanConant was very sensitive to her feelings and kept her informed throughout the entire process.

“Part of it was a difference in time,” Saruga said. “Part of it was he was good at his job.”

After speaking to two witnesses and Saruga to put together a narrative, VanConant began looking into the suspect's past.

VanConant found an incident report from 1987 in Gibraltar, Michigan. The man was arrested for breaking and entering. Police believe he got in by tearing out a screen and entering through a window. The homeowner heard a noise, and when he went downstairs to investigate, he found the man in the laundry room, naked from the waist down, with his wife’s bras and a blouse. The police found the man’s clothes, along with multiple pairs of women’s underwear in his car.

The man was convicted and served his probation.

The incident was expunged from his criminal record.

Life after trauma

Saruga had two rules in her house when her sons were growing up: don’t scream unless you actually mean it, and never wear a ski mask. This led her sons to believe that something happened to her, but they never knew what.

“I was kind of glad they were sheltered from that,” she said. “They didn’t have those images of Mom.”

When Saruga found out her case was reopened, she went into shock. She started crying uncontrollably in her home. Her husband called her youngest son and asked him to come to the house.

Her son came without saying anything. He just held her.

“When a severe trauma happens, life gets split in two – before and after,” she said. “My son was a reminder that there was an after; that we survived and things were good.”

For 35 years Saruga had accepted that the person who raped her would not face trial for what he did to her. After CMUPD contacted her, she said she felt hopeful that she might finally see justice done.

On Sept. 26, 2018, Det. VanConant turned her life upside down for a second time.

He told her the case against her attacker had been dismissed.

Even though VanConant spent months gathering information, and collected enough evidence to request a warrant, the request was denied because the statute of limitations had expired.

In 1983, the statute of limitations was six years. Nobody could be charged with the crime after October 1989. Although Saruga will never have her case tried in court, she said the CMU Police Department and the Michigan Attorney General’s Office are working hard to find other victims. The goal is to get the man’s DNA entered into the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS) to see if he is connected to any other unsolved rape cases.

After the warrant request was denied, VanConant distributed a message to multiple police agencies about Saruga's case and the possibility of other similar cases. According to his report, two agencies responded with plans to find DNA evidence for similar rape cases around the time of Saruga's. VanConant wrote that if the man is involved in any other unsolved crimes, he will be identified through CODIS.

The man accused of raping her will never be arrested for the crime he committed against her. However, he is aware of the attempt to bring charges against him and that he has been connected to Saruga's case.

“As a result of the case being reopened, he’s free and I have to have constant security,” she said.

Demanding changes

Saruga doesn't want other unsolved cases to end like hers. She has been working in Lansing to make sure other perpetrators don’t walk free because of statutes of limitations.

"Rape culture is perpetuated by so many things," she said. “One of those is that we have laws that don’t allow prosecutors to prosecute."

She proposed an amendment to Michigan’s law that would change the statute of limitations for any crime punishable by life in prison in the state of Michigan. The crimes included in the amendment are murder, conspiracy to commit murder, solicitation to commit murder, criminal sexual conduct in the first degree and a violation of the Michigan anti-terrorism act.

Saruga’s proposed amendment says, ”If the offense is reported to a police agency within one year after the offense is committed and the individual who committed the offense is unknown, an indictment for that offense may be found and filed within 10 years after the individual is identified.”

The language in this amendment is based on Brandon D’Annunzio’s law, which applies to kidnapping, extortion, assault with intent to commit murder, attempted murder, manslaughter or first-degree home invasion. Saruga said the law doesn’t apply to felonies of a higher degree, which is what her proposed amendment is asking for.

The key to this proposed amendment, Saruga said, is making the law retroactive, meaning it can apply to crimes where the statute of limitations has already expired. The retroactivity would affect cold cases from 1995 and earlier when these high-degree felonies still did have a statute of limitations.

Her proposal has gained a lot of support, Saruga said. She is working with the Michigan Coalition to End Domestic and Sexual Violence, the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network (RAINN), the Prosecuting Attorneys Association of Michigan and state legislators to help rape victims get justice.

"There really is a team coming together," she said.

"My Name is Lisa"

Saruga is sharing her story outside of Lansing as well.

After quitting her job at her church in January 2019, Saruga has focused all of her attention on writing. Her goal was to write at least 20 hours each week, although she often went well over. She said she would usually start writing at noon, and at dinner time, her husband would bring dinner to her desk. She would eat while she wrote, and then continue writing until 3 a.m.

“It just kind of flowed,” she said. “It was all in my head and it was easy to keep pouring out on paper.”

As soon as her case was reopened, Saruga felt like everything was turned upside down. She wanted to keep track of how she was feeling, so she bought a black-page journal and a white pen to journal.

During the investigation, she almost filled the entire journal. She had just one page left the day she found out the case was dismissed. She filled that page and purchased another journal, which was about the aftermath of the dismissal.

Because her case became well-known among police agencies and legislators, she was encouraged to write a book about her experience.

“When someone said I should write a book, I had two full black journals that were basically the book,” she said.

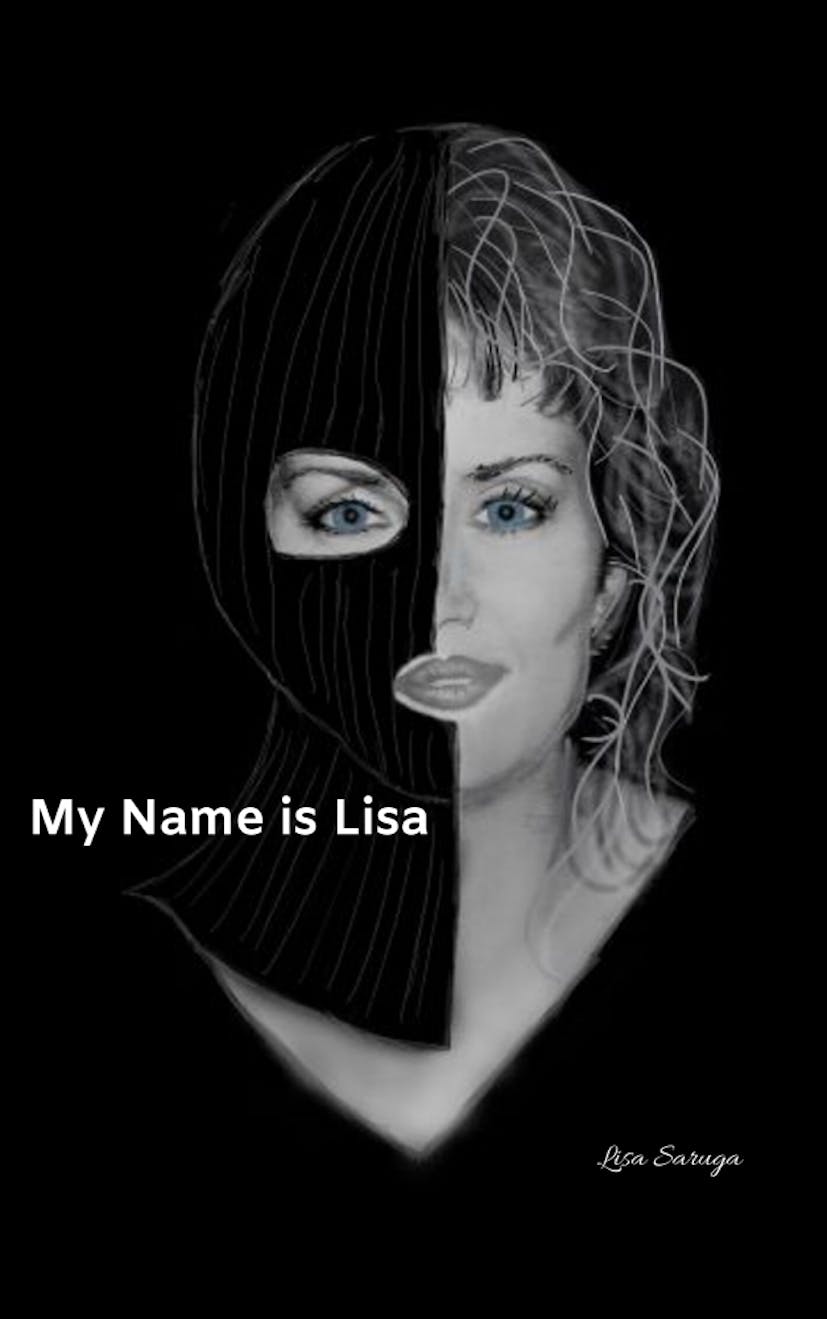

She finished her book in two months. The book, titled “My name is Lisa,” described her experience from a Christian perspective. She wrote about how God helped her make peace with the situation, and she also used her background in counseling and political advocacy to write about the legal system and victim’s rights.

The cover of Lisa Saruga's book about her experiences. Courtesy Photo | Lisa Saruga

After writing the book, Saruga planned to put it on the shelf and focus on getting it published later. However, when she met someone whose grandfather worked for Zondervan Publishing, her path to becoming an author was set in motion.

Saruga said she began working with Cindy Lambert, a Christian writer and editor, to get her book ready for publication. This summer, Saruga attended a writer's conference, where her book was used as an example in a mock publishing board. Within 48 hours, she said she got calls from every agent and publisher there.

She chose Wes Yoder as her agent. Yoder founded Ambassador Speakers, Inc., a company that represents Christian speakers in the United States.

Saruga said her agent has submitted her book to six publishers, and will be signing with one in the next few weeks.

"It's surreal, I cannot believe the attention (my book has) received so far," she said.

While it won't be confirmed until she officially signs with a publisher, Saruga believes "My Name is Lisa" will be on bookstore shelves next spring or summer.

In the meantime, Saruga has been writing blogs on her website. She said she has a new website launching in a few weeks where visitors can download a free e-book she wrote about rape culture.

She is also highly active on social media, promoting work from other sexual assault advocates and providing a voice to other survivors of sexual assault. She just registered the hashtag, #MyNameIsLisa, for survivors whose perpetrators are free and unincarcerated.

"I just want to raise awareness," Saruga said. "This was on the front page of the paper, it got solved and there's hope for those who experience this."