Cracking the case: CMU police use phone-hacking technology to bust crime

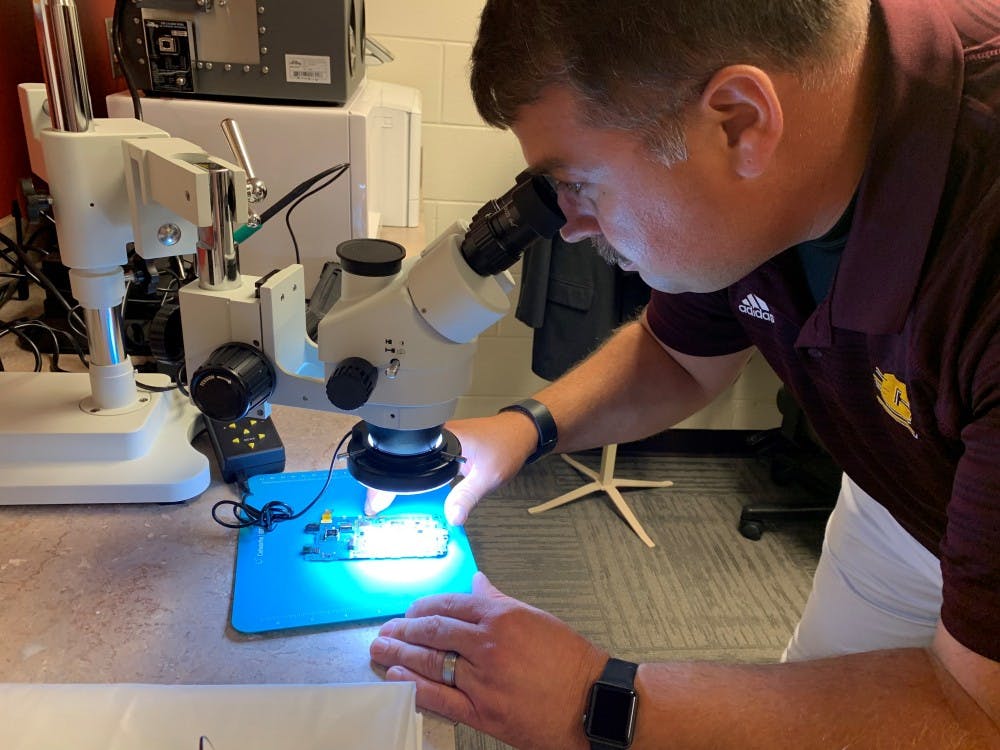

Central Michigan University Police Detective Jason VanConant shows how uses a microscope to solder wires to a cell phone for data extraction. (Central Michigan Life | Melissa Frick)

Central Michigan University Police Department has a new kind of weapon in its arsenal to bust crime: A detective with the ability to hack locked cell phones.

After receiving four weeks of training last month at the National Computer Forensics Institute in Alabama, CMUPD Det. Jason VanConant is now able to extract and download information from cell phones, even without a passcode.

VanConant, who has worked with CMUPD for three years, was trained by the U.S. Secret Service to extract data from cell phones without needing a password. He is now the only detective at CMUPD, and one of the few in Mid-Michigan, with this kind of unique cell phone forensics training, giving university police the ability to crack cases in a day that would have previously taken weeks to figure out.

While VanConant already had some prior knowledge of how to extract data from cell phones, the Mobile Device Extraction class focused on working around a passcode to hack a phone.

Cell phone data is stored in a tiny chip inside the device, VanConant explained. To retrieve data from a phone without its password, an expert must be able to take apart the phone and connect wires to the chip to extract the data.

Once the data is extracted, it is downloaded into a searchable database where CMU police can search key words, making it easier to search through the tons of extracted data.

VanConant said the phone is pretty much unusable after the data has been extracted, so officers need to obtain a search warrant before hacking the phone.

There are two possible scenarios when police want to extract data from a phone, VanConant said: If someone is a victim in a situation and wants police to investigate, the victim can consent and allow an officer to search their phone.

On the other hand, if someone has been involved in a crime and isn't being cooperative, a police officer can legally seize the phone without a warrant to prevent evidence from being destroyed, he said.

"Once I’ve seized it, if you’re not cooperative, I would try to get a warrant and get legal permission to extract the phone," he said.

Cell phones are an integral part of most cases, VanConant said, because they contain a wealth of information about people's lives.

"Cell phones are involved in just about every case that we do," he said. "Everybody communicates through their cell phone. This technology could be used for everything from abduction to domestic to drug crimes, assaults. People confess to other people on their phones."

While the training he received isn’t necessarily new or groundbreaking, the technology isn’t easily accessible to police officers, VanConant said. That’s why the training is so helpful to CMUPD, he said – it will give officers access to data that took much longer to obtain before.

In the past, the only cell phone forensics team in the area was the Michigan State Police department. Because MSP had the only mobile device extraction team in Mid-Michigan, their services were highly sought after by police agencies around the state.

"Normally we would send our cases over to MSP crime lab, and it would be a 4-6 week turnaround," VanConant said. "Here, I can do it in a day."

Because VanConant is one of the few detectives in the area who is trained to extract data from cell phones, he is often sent cases from other police agencies who need to hack a locked phone.

CMU Police Lt. Cameron Wassman said VanConant deals with several cases each week where he assists other agencies with data extraction.

"It's been incredibly valuable, not only to us but to other police forces," Wassman said. "So many cases involve technology these days. We're fortunate we had the ability to send him; it's been an incredible asset."

Central Michigan University Police Detective Jason VanConant shows the soldering iron he uses to apart a cell phone to extract data. (Central Michigan Life | Melissa Frick)

Along with receiving training by the U.S. Secret Service, VanConant also received new equipment to extract data from cell phones, including a microscope and a soldering iron.

VanConant had to be put on a waiting list prior to receiving the training, which is completely paid for by U.S. Secret Service.

But for VanConant, who has always had an interest in forensics, the wait was worth it.

"This stuff is very useful," he said. "It’s imperative (to our work) because every case deals with technology. Not only extracting data from cell phones is important, but the speed at which we can do it. We don’t have to wait six weeks for a crime anymore, so that's a big plus."

When it comes to cracking cases on a university police force, the detective said timing is key.

"We don’t have six weeks when it comes to crime," he said. "In the campus world, six weeks is half a semester. We don’t have that kind of time with students coming and going, so quicker is better for us."