Sexual assault at CMU: The Title IX office, SAPA and CMUPD are a few of the resources here to help if you are sexually assaulted

April is Sexual Assault Awareness Month at Central Michigan University, but by the time speakers arrive on campus and education efforts begin, a number of students will already have been sexually assaulted.

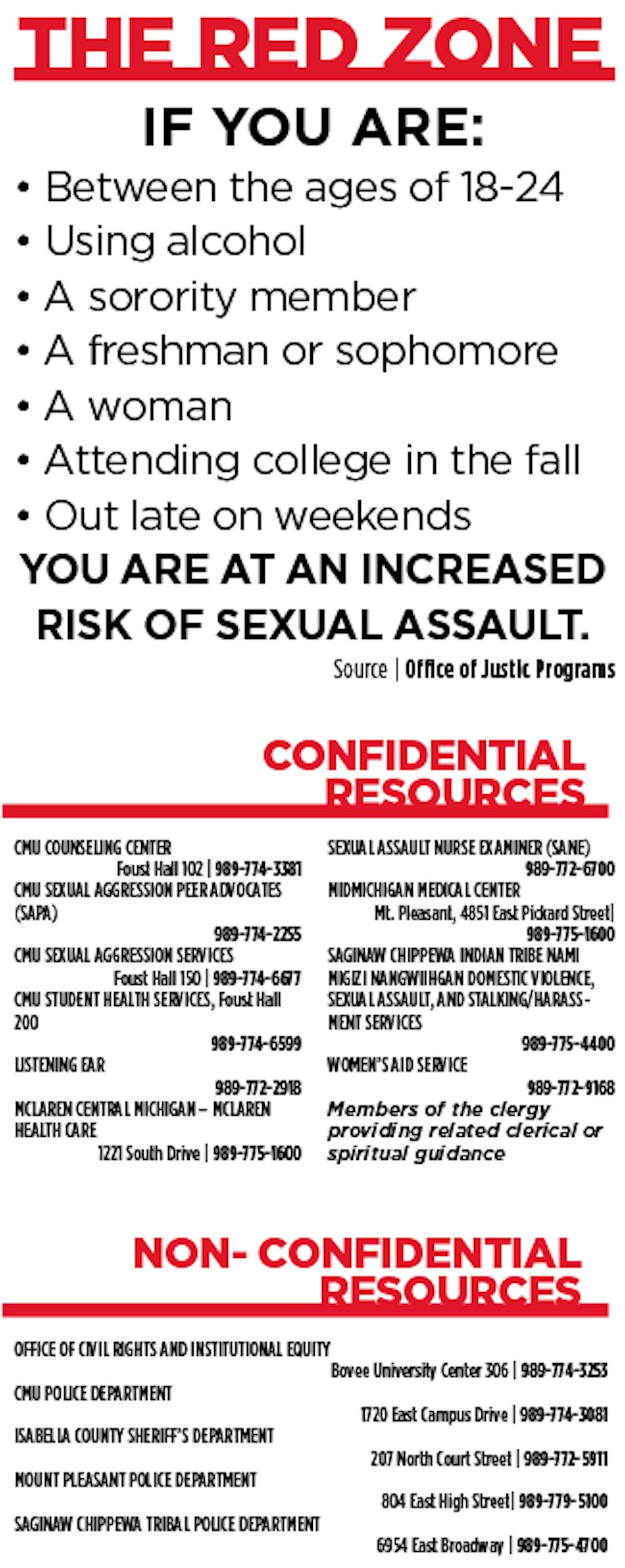

According to Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network (RAINN), more than 50 percent of college sexual assaults occur in either August, September, October or November, shortly after the fall semester begins. This dangerous time period is known as the “red zone.”

This time, when many young adults are finding themselves without adult supervision, maybe for the first time in their life, is a time when there is increased partying, alcohol consumption, the meeting of new people and other circumstantial events that can increase students risks of being sexually assaulted.

College-aged victims of sexual violence often don’t report the incidents to law enforcement, according to RAINN, making it almost impossible to total the number of assaults in the area. Add to that the difficultly of obtaining information about those sexual assaults and it makes it harder to paint an accurate picture of what is happening in regards to sexual assault on CMU's campus.

CMU learned of a recent sexual assault incident on Thursday, Oct. 4. At about 4 p.m. on Oct. 5, CMU sent out an email to all students, faculty and staff notifying them the incident had occurred on campus. The sexual assault is said to have taken place Sept. 17 between 9:30 p.m. and 10 p.m. near the large rock between Brooks Hall, Music Building and Park Library. The email stated a man approached a student, asked about a music festival and then assaulted her.

The email notice was a surprise and was an unusual response by the university.

When CMU’s chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists submitted a Freedom of Information Act request to the university last semester asking for policies and incident reports regarding campus sexual assaults, they were outright denied, citing the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act. FERPA is a federal law that protects the privacy of student education records and frequently cited by CMU when it denies records requests.

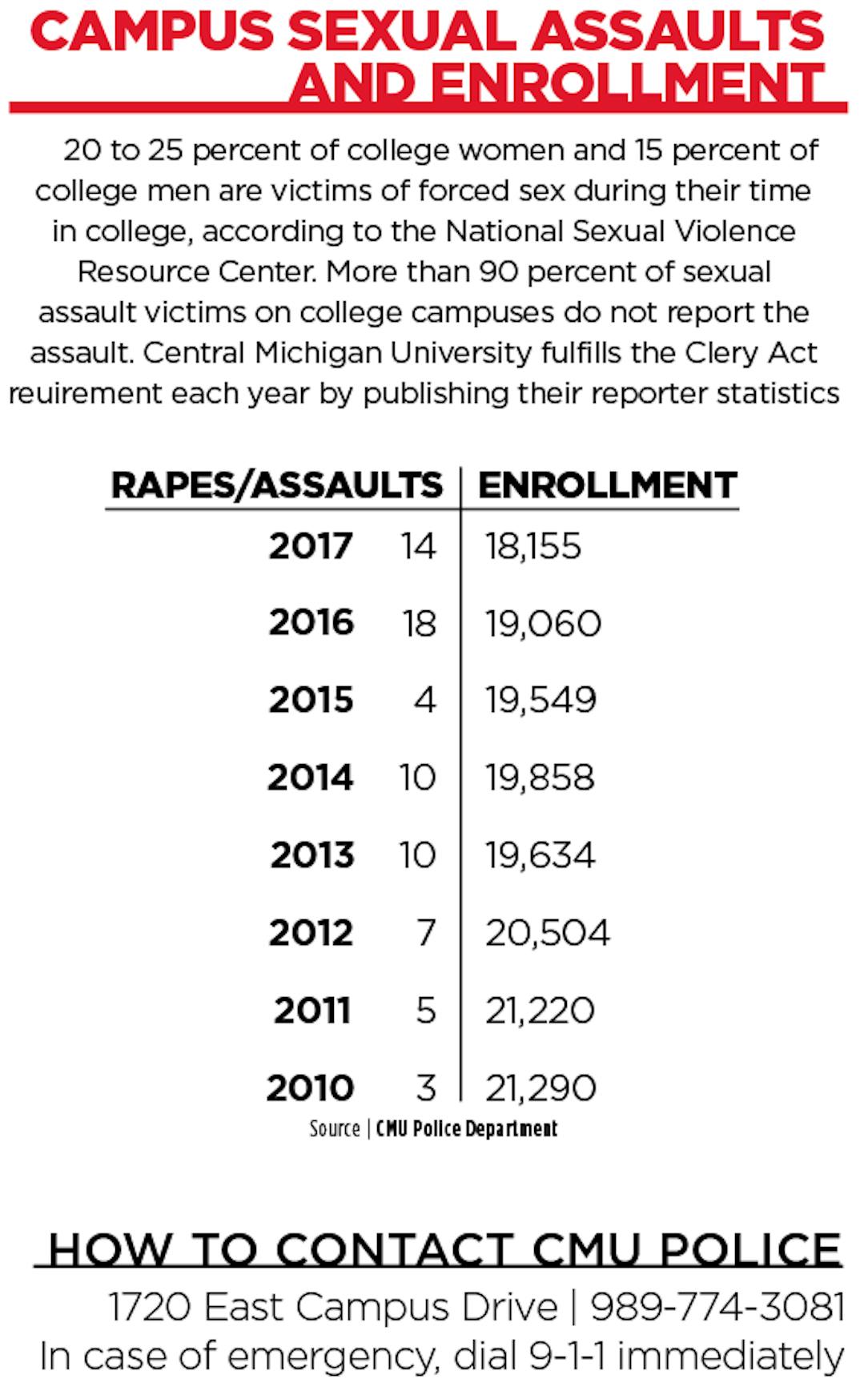

According to the October 2018 Annual Fire and Safety report – CMU's report that fulfills the Cleary Act requirements – there were 14 total rape incidents between on and off-campus locations in 2017. That's down from 18 incidents in 2016.

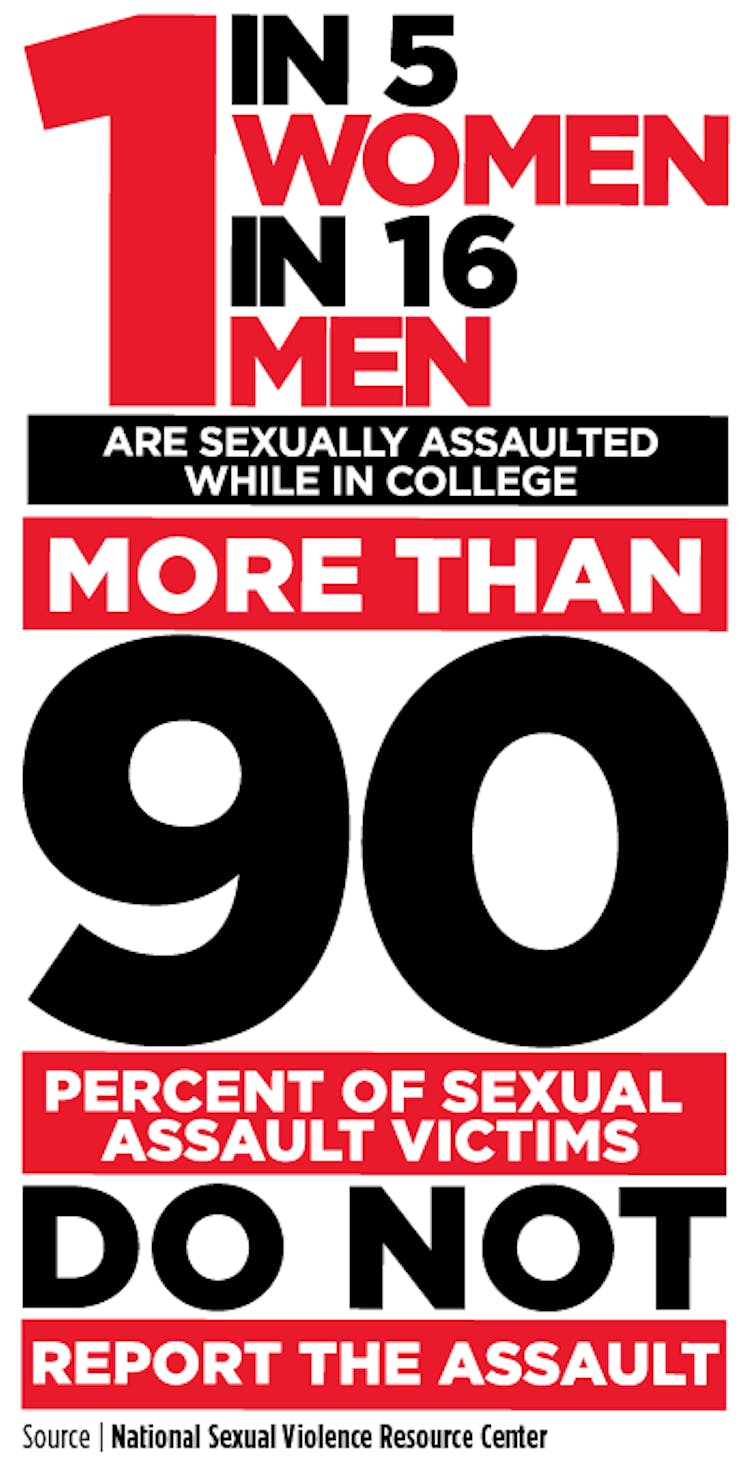

On a campus of 18,000 students that is less that two assaults per month during the academic calendar year, according to the university's numbers. But according to the National Sexual Violence Resource Center, 20 to 25 percent of college women and 15 percent of college men are victims of forced sex during their time in college, while more than 90 percent of sexual assault victims on college campuses do not report the assault.

If students aren’t coming forward about their experiences, people should ask them if they trust their administration, said Annie Clark, civil rights activist and co-founder of End Rape On Campus (EROC).

“If they don’t trust the administration they’re not going to come forward,” Clark said.

EROC's mission is to end campus sexual violence through direct support for survivors and their communities, prevention through education and policy reform at the campus, local, state, and federal levels.

“Students know they have the right to report and what we’re actually seeing now is numbers go up,” Clark said. “Often times administrators or parents, or potential students, see that as a bad sign when in reality, those numbers that are higher more accurately reflect what’s going on, on a college campus.”

Clark, a sexual assault survivor, led a nationwide campaign forcing universities around the country to address sexual assault more aggressively, inspiring the 2015 CNN Films documentary, “The Hunting Ground.”

While she has watched the American attitude about sexual assault shift toward supporting survivors since the 2011 Dear Colleague Letter issued by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights demanding universities uphold federal policies, she said she believes we still live in a victim-blaming society. While uplifting and changing deeply-rooted American ideas about sexual violence might still require decades of advocacy from people like Clark, it might be important to understand how to navigate the system and resources put in place by your university in the meantime.

Whether a survivor of sexual violence chooses to make their incident public or not is an individual decision, but the responsibility of a university to address the needs of that survivor are required.

What is sexual assault and who is at risk?

Sexual assault, as defined by CMU, is “touching of a sexual nature without consent.” It encompasses a wide range of acts. It includes sexual harassment, sexual exploitation, domestic violence and stalking.

According to the National Institute of Justice, a development and evaluation agency of the U.S. Department of Justice, college freshman and sophomore students are at higher risk for a sexual assault. More than half of sexual assaults take place on weekends and more than half of those occur between midnight and 6 a.m., according to NIJ.

CMU Police Lt. Larry Klaus said students have a lot to deal with – classes, homework, jobs, finances, maintaining a social life and well-being. The added trauma of an sexual assault can push students past their breaking point. According to Mental Health America, people who experience sexual assault are at an increased risk of developing depression, PTSD, anxiety, eating disorders and substance abuse disorders.

It's important that all students – especially those supporting sexual assault survivors – understand what resources are in place at CMU that can help you.

Title IX: What to do if you're sexually assaulted

All schools that receive federal funding in the U.S. are required to follow Title IX, a civil rights law that ensures equal education access for all students and prohibits gender discrimination.

“When a student has experienced a hostile environment such as sexual assault or severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive sexual harassment, schools must stop the discrimination, prevent its recurrence and address its effects,” according to the EROC website.

The Office of Civil Rights and Institutional Equity (OCRIE) at CMU, which includes the Title IX office, is located in the Bovee University Center, room 306. The OCRIE office is where a student would need to go to in order to file a report with the university and receive advice regarding the policies and procedures. It also acts as a place of resolution for complaints of discrimination. CMU has its own set of guidelines, the sexual misconduct policy, that it follows for carrying out these policies and procedures.

Title IX protects against discrimination regardless of whether the incident occurs on campus or not, and even when the people involved are not students. However, if the person accused of violating the policy – the respondent – is not affiliated with the university, reporting with a police department would be a better option than carrying out an investigation with the school, said Katherine Lasher, CMU's Title IX coordinator and executive director of OCRIE.

"The university can only make decisions with respect to the individuals that are students here or who are working here," Lasher said.

Lasher receives the reports of sexual misconduct and is therefore a resource to every CMU student.

"We want to ensure that everyone has an understanding of what's available to them so that they are empowered to make the decisions and can decide for themselves what's gong to be the best course for them," Lasher said.

If a student wishes to speak with someone in the Title IX office they can call, email or utilize CMU's online reporting tool. However Lasher said the most effective way is to set up an appointment to ensure someone will be available to talk. During the initial meeting, a student will be given resources, options and ways to seek help and only when a student decides to go through the school's investigative process, would he or she have to explain their personal experience.

"Our goal is only for the survivor to have to tell their story one time," Lasher said.

According to a survey conducted in the 2015-16 academic year by Mary Senter, CMU faculty member and director of the Center for Applied Research and Rural Studies, 76 percent of students surveyed did not know where the OCRIE office was located and only 18 percent knew how to contact the Title IX coordinator. For the survey, the Office of Information Technology drew a random sample of about 4,750 undergraduates, who were enrolled on the Mount Pleasant campus in Fall 2015.

In addition to OCRIE, there are other confidential and non-confidential resources on and off campus that students and community members can seek out. If a student wishes to keep their experience private, they would not want to report to a non-confidential source, who may have an obligation to relay the information.

According to CMU's sexual misconduct policy, all CMU staff, faculty, and student employees are required to report any information they know about possible sexual misconduct to the Title IX Coordinator. The exceptions are people employed directly by confidential resources or employed as journalists at CMU. Other exceptions include details shared during class discussion or during public demonstration nights, such as Take Back the Night, an annual rally event against sexual assault.

CMUPD, a non-confidential source, advises victims to stay as calm as possible if attacked and to evaluate resources. Following an attack, they suggest to get to a safe place and call the police.

In the interest of preserving evidence of the assault, CMUPD advises to not shower, bathe or change your clothes until you can receive a sexual assault forensic exam, which must be administered by a Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE) within five days (120 hours) of the incident.

Klaus recommends that all victims of sexual assault get a SANE exam, regardless of whether they want to prosecute at that time or not. During the process, the examiner will not only collect evidence, but they will also check for STI’s, pregnancy and help provide resources, Klaus said. Once administered, the evidence is required to be maintained by the medical center by law, for up to one year.

These exams can be administered for free by trained professionals at McLaren Central Michigan Hospital at 1221 South Drive, in Mount Pleasant.

“The importance of filing a report is if there’s an offender on our campus that’s assaulting victims we want to know who that individual is, and they need to be stopped,” Klaus said.

Victims of sexual assault who hesitate to report due to unlawful use of alcohol or drugs during the time of their assault should know that under CMU’s sexual misconduct policy, it states that the Office of Student Conduct will not pursue disciplinary action against this kind of behavior if the complaint made is a “good faith report.” The CMUPD has a practice of not pursuing these charges as well.

Resources

Non-confidential resources include OCRIE, CMUPD, Mount Pleasant Police Department, Isabella County Sheriff’s Department and the Saginaw Chippewa Tribal Police Department.

Confidential resources include Sexual Aggression Peer Advocates, CMU Student Health Services and hospitals.

“There’s a lot of support throughout this campus and we want to see our survivors recover and we want to see our students be successful,” Klaus said.

Within the CMUPD there is a special victims investigation cadre made up of officers and detectives, who are trained to “better respond and work with survivors of sexual assault, dating domestic violence, and stalking.”

They take a victim-centered approach where the goal is to help each survivor get “back on track and find advocates to help them navigate the university system.”

"When we’re working with survivors we tell them, ‘it’s not your fault and we believe you,’” Klaus said.

CMUPD likes to give survivors a few sleep cycles to process any trauma before proceeding with interviews, Klaus said.

SAPA is a 24/7 survivor-centered, paraprofessional student organization that offers services that include a confidential support line, online chats and direct in-person services, throughout the fall and spring semesters.

Members of SAPA help provide survivors with a step-by-step explanation of all of the options they have, from counseling referrals to medical and law enforcement assistance.

“Sometimes it just depends on how long people want to talk – but to really explain what each step would look like so that they’re making the best decision with most information that they can get and what it would look like,” said Brooke Oliver-Hempenstall, director of Sexual Aggression Services.

On average, SAPA receives six contacts, or people who utilize their services, per week throughout the school year. Oliver-Hempenstall said during the fall there is a slight increase in contacts. While it coincides with the “red zone,” she attributes this increase in interest to new and returning students who are either discovering resources like SAPA for the first time or are utilizing resources based on trauma that was experienced during the summer.

She also said that many students come to CMU with no prior knowledge of what sexual assault is and at the same time that are finding out what is, they are realizing they have been victims of it in the past.

Oliver-Hempenstall, Klaus and Clark all agree that sexual violence education needs to happen long before coming to college.

“If we’re starting to talk about sexual violence in first-year orientation it’s way way too late,” Clark said.

SAPA is responsible for several educational outreach programs including No Zebras, No Excuses, a mandatory performance-based training during freshman and transfer orientation; education for student groups, fraternities and sororities, university organizations and sports teams; and events like ice skating and yoga to get the heavy topic of sexual assault in front of all audiences.

"We try to do things that are yes informative and educational, but then we just want folks to know that we are here and that you know how to reach us,” Oliver-Hempenstall said.

In addition to on-campus resources, Listening Ear Crisis Center is a private, non-profit based in Mount Pleasant that can offer support and advocacy.

When asked about how these resources are making students feel comfortable about coming forward and seeking help, Oliver-Hempenstall said she believes that the simple fact of the university supporting resources like SAPA shows that the institution is willing to have these conversations.

“Stuff is happening at all schools around the nation,” she said. “I appreciate the fact that CMU is comfortable having these conversations, having these supports so that folks who – whether they want to disclose and report to the authorities, to the school to investigate, for counseling – that they’ve provided the options and I think that it helps folks feel more comfortable perhaps in reporting because they know that they’re supported in doing so.”