SPECIAL REPORT: Student Media Climate Change Coverage

Experts discuss impact of a warming planet on a global and local scale

Click on one of the buttons above to jump to that story

Warmer temperatures contribute to billion-dollar weather and climate disasters

Zahra Ahmad

Wetter-than-normal conditions in the fall months mean trouble for Mid-Michigan farmers growing standing crops such as soybeans and corn.

Union Township farmer Randy Recker, who has been growing soybeans, wheat and corn for more than 45 years, said the rain his farm received in October was almost as problematic as the flooding that occurred in June. Over the course of 10 days in October, Isabella County received 11 inches of rain. For Recker that meant having to wait for water to recede before he was able to harvest his soybeans.

“When you get rain in the fall, it's hard for it to go away,” he said. “In the summer, it’ll go away because it's warmer—it evaporates."

A severe storm in June caused an estimated $10-15 million in crop damage for farmers in Isabella County, according to Paul Gross, an educator for the Michigan State University Extension, though a final total isn't expected until January 2018, when crop yields are totaled. Most crops have been harvested as of Nov. 30. The storm is said to be the county’s most costly agricultural disaster.

Storms like one experienced by Mount Pleasant residents this summer are occurring more frequently across the nation.

Since 1980, the United States of America has sustained 218 climate and extreme weather events that have caused an overall $1 billion in damage per storm. More than half of those natural disasters occurred in the past decade.

Those massive storms resulted in $1.2 trillion in recovery costs. That total doesn't include the estimated $200 billion in damage caused by Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria which have taken place since September.

“It’s been a prolific year for big disasters,” according to Russell Vose, a physical scientist for The National Centers for Environmental Information. Vose said 2017 ties 2011 for the most billion-dollar disasters – 15 – that occurred between January and September in America.

A draft of the National Climate Change Report, awaiting approval by President Donald Trump, states temperature and precipitation extremes caused by a rise in global average temperatures can affect the likelihood of disasters and extreme weather.

“We can’t say these climate and weather disasters have been caused by climate change,” Vose said. “There have been some studies released in recent years that said ‘these particular events are being influenced by the climate’.”

What does climate change mean?

Confusion about the science of climate change often stems from not understanding the difference between "weather" and "climate."

Daria Kluver, Professor of Meteorology at Central Michigan University

"Weather is what (conditions are) day-to-day outside," said Daria Kluver, a professor of meteorology. "Climate is the long-term, aggregate statistics of the weather."

Climate is always changing, Kluver explained, but the science surrounding climate change in the national conversation seems to focus on whether humans are contributing to the changes in a significant way.

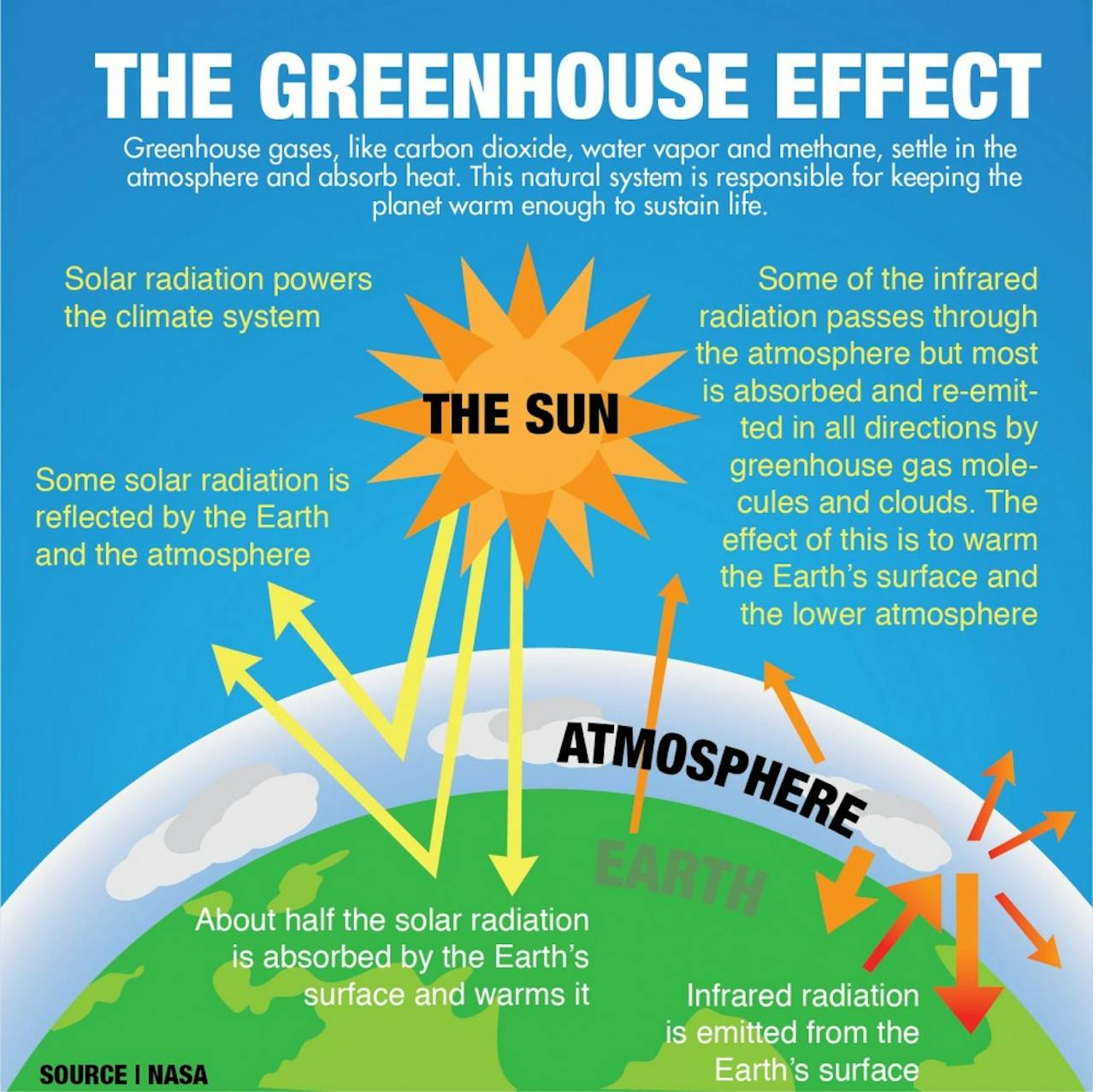

"Climate can change because of natural reasons — volcanic eruptions cool the climate for a few years (and) the amount of energy the sun puts out, such as solar flares, can change the climate," Kluver said. "(Human) changes are things like emitting greenhouse gases, deforestation and changing the surfaces of the earth so they absorb more or less radiation."

The vast majority of climate scientists report that human activity significantly contributes to climate change. According to the Climate Change 2014 Synthesis Report Summary, greenhouse gas emissions are at a historic high level and have increased largely as a result of economic development and the growing human population.

Greenhouse gases, like carbon dioxide and water vapor, settle in the atmosphere. These gases absorb heat emitted from the Earth's surface. This natural system, the “Greenhouse Effect,” is responsible for keeping the planet warm enough to sustain life.

"Think of the atmosphere as a giant sponge that traps energy in the form of heat, which warms the Earth," Kluver said. “If the atmosphere didn't exist around the Earth, all of that energy would be released into space. None of it would be retained and the planet would be very cold."

The Greenhouse Effect is warming at an alarming rate, Kluver explained. The global temperature is rapidly increasing due to massive releases of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Human-made industrial processes and burning of fossil fuels accounts for 78 percent of greenhouses gases in atmosphere today, according to the climate change report.

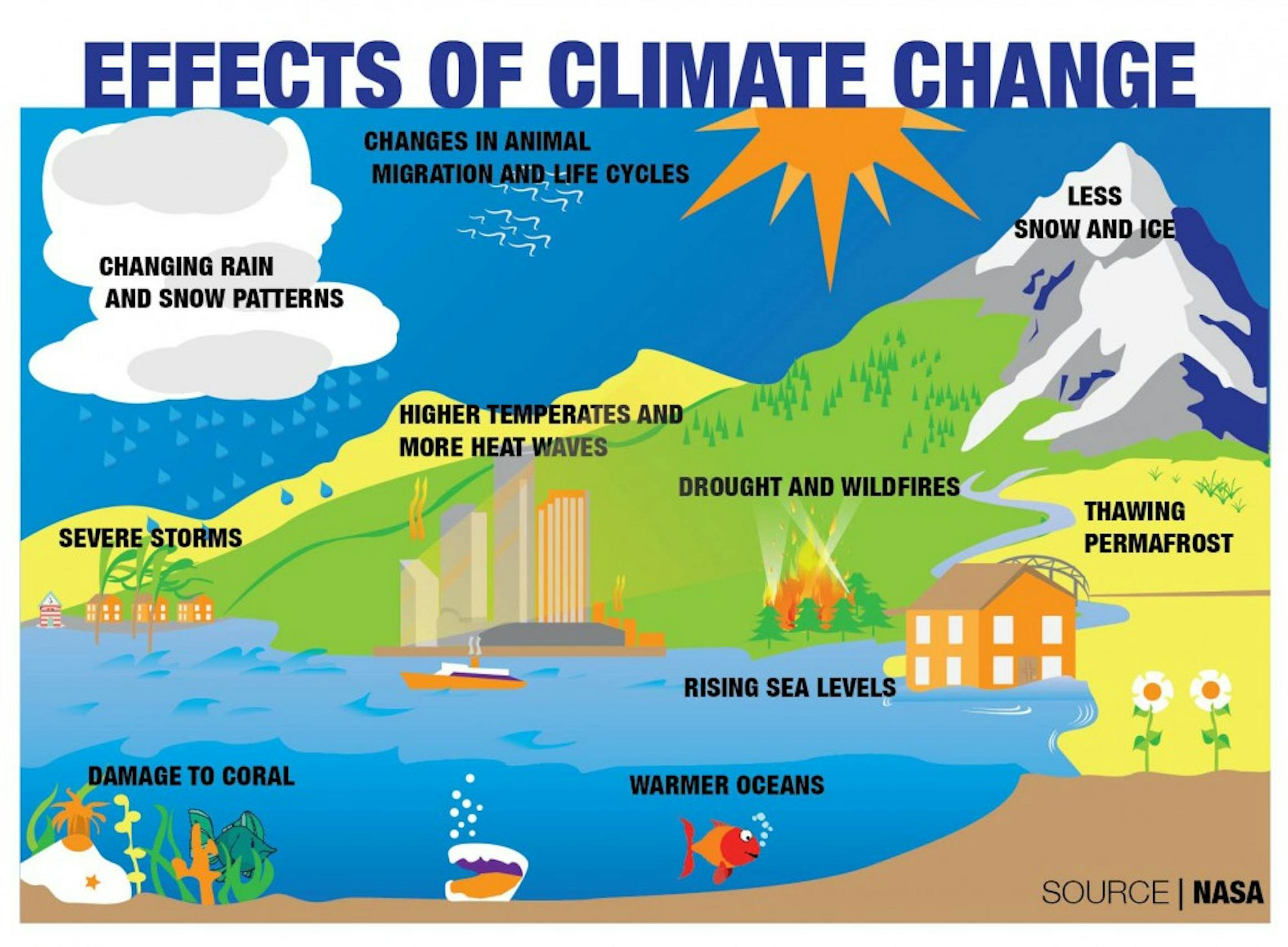

Global temperature data shows that climate change will have drastic affects on the planet’s ecosystems, Kluver said. Ocean levels will continue to rise. Weather will become increasingly erratic if the activity contributing to global warming is not reduced.

"The climate is going to change so much that global populations will have to move if they live by the shore or on islands," she said. "This could potentially result in horrible things (involving) famines, agriculture and immigration due to sea level rising."

Temperatures may increase 4 degrees Celsius by 2100.

"That's really warm," Kluver said. "You're probably thinking four degrees isn't a lot, but we're talking global average temperature."

To put the increase into perspective, Kluver described during the last ice age, 18,000 years ago, the global temperature was only 5-8 degrees Celsius lower than the average temperature today.

Melting ice sheets from Greenland and the Antarctic are the biggest contributor to the rising sea-level resulting from climate change. Kluver said this will have the greatest impact on humanity.

"People love to live by the sea," she said. "The costal ecosystems, and life that is there, will be impacted. In some cases, salt water from the ocean can be introduced into freshwater systems as a result of severe flooding."

State of the climate

Extreme weather certainly has become a topic of national media coverage. Record hot days are becoming more frequent. Nationally, winters are becoming shorter though sometimes more intense. Wildfire season threatens the western states for longer than ever before.

According to data collected by the NCEI the likelihood of drought, flooding and severe storm disasters has increased overall in just the past decade.

Data from NCEI shows that since 1980 more than half of the recorded wildfires, severe storms, and flooding disasters exceeding $1 billion in damage have occurred in the past decade.

Scientists don’t have effective forecasting models to prove climate is causing weather disasters. That's because the weather systems form quickly and don't follow a historic trend. What is known, Vose said, is that national and global average temperatures have been breaking historic records.

“Every decade is hotter than the decade is proceeds," Vose said. "It’s been at a steady pace like this for the past five decades."

Humans influencing climate change

Earth’s first breathable atmosphere formed about 500 million years ago. Since then, its climate system has maintained a radiative equilibrium, or balanced the amount of energy coming into and out of the atmosphere.

Radiation entering Earth’s atmosphere travels in the form of short wavelength solar radiation. Only about 46 percent of the energy entering the atmosphere reaches Earth’s surface. The rest is absorbed by clouds, scattered, or reflected back into space.

In order to balance the amount of energy, known as the "net energy at the top of the atmosphere," the radiation leaving the atmosphere must be the same as the amount being emitted to Earth. This balance is currently off.

The net energy of the atmosphere can be thrown off as a result of natural processes like variations in the Earth’s orbit (Milankovitch cycles) and anthropogenic, human caused, climate forcing.

“The natural changes in climate are very slow, occurring over 1,000-year to 10,000-year periods,” said Richard Mower, a meteorology professor. “What we’re seeing now is a very rapid climate change.”

Richard Neil Mower, Professor of Meteorology at Central Michigan University

Scientists have run climate models without the influence of human impact, Mower said. Those models have shown that without the influence of carbon dioxide the Earth should be experiencing relatively cooler temperatures today. This indicates the change in climate being observed today can’t be contributed to natural processes alone.

According to a temperature analysis conducted by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) the average global temperature has increased about 1.4 degrees Fahrenheit since 1880. The rise in global temperatures correlates with an increase of carbon dioxide.

Researchers defend their science

Frustration among young researchers and scientists is growing as some political leaders continue to deny the severity of climate change.

Dean Horton, a doctorate student studying microbiology at CMU, cited an executive order issued on Jan. 20 banning any federal agencies dealing with research from speaking to the press or releasing their data to the public on platforms such as websites or social media. The ban was lifted nearly two weeks later.

Preventing research from being published, or in any way inhibiting research, harms more than just America. As a leader in scientific research, Horton said if American scientists work is censored, the world of science as a whole is set back.

“If you censor results, or inhibit research from being conducted, it impacts everyone,” Horton said. “In the scientific community, scientists share knowledge with one another regardless if you’re part of a federal agency or academic research.”

Researchers working for federal agencies have always been subject to some degree of censorship. Director of the Institute for Great Lakes Research Donald Uzarski said it is times like these where he feels most for his colleagues who work for the government. Their research funding relies on their cooperation with their administrators, he explained.

“Censorship is not a good thing. It doesn’t belong in science, ever,” Uzarski said. “However, censorship has always been there to some degree. Federal scientists have never had the ability to report on their science as freely as scientists in academia.”

A recent National Public Radio (NRP) analysis of grants awarded by the National Science Foundation found that scientist applying for public grants are "self-censoring" by removing the term "climate change," from their proposals.

The current administration's stance on climate change was made public when the U.S. was pulled from the Paris Climate Accord. The President's 2018 budget proposal, eliminating climate science funding, has left climatologists in a difficult position.

For climatologists, it can be frustrating to have to continuously defend evidence-based science against the opinions aired in the media by people who don’t have backgrounds in that science.

"I think the current administration is ignoring clear evidence of climate change — the impacts it will have on the people living in this country," Kluver said. "They're making decisions they think will benefit them right now. In the long run, they're jeopardizing the safety of the people in this country."

Changing climate, extreme weather will have significant effect on Michigan agriculture, Great Lakes ecology

Zahra Ahmad

When climate change is discussed, its impact is often presented in global terms – the rising of ocean levels or the melting of polar ice sheets. In Michigan, the Great Lakes also are being impacted in significant ways that fewer people seem to be aware of.

According to a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency report published in January, ice cover on the Great Lakes is forming later and melting sooner as a result of rising global temperatures. That could impact life in Michigan in several ways – including a lack of snow for winter tourism and precipitation carrying more contaminants into the lakes through runoff.

“While we’ve seen a decrease in the amount of regular snow received, we’re seeing an increase in lake effect snow," said Daria Kluver, a meteorology professor studying lake effect snow.

Michigan is receiving more lake effect snow because of warmer lake temperatures. The temperature in Michigan has increased by 1.1 degrees Fahrenheit since the 1980s, Kluver said, and it is predicted to get warmer.

When cold air crosses over a warm lake, moisture is picked up and condensed into clouds. Those systems dump snow downwind of the lake when it passes over the cold land. As global and national temperatures continue to rise, less precipitation in Michigan will fall as snow and more will fall as rain. Total precipitation across the Great Lake states has increased by 11 percent since the beginning of the century.

Data released by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) suggests the Great Lakes could remain ice-free for longer periods of time.

Changing Great Lakes

Heavier rain storms are projected to increase as the impacts of climate change become more profound, according to NOAA. This increase becomes problematic to areas prone to flooding.

“The biggest issues facing the Great Lakes (are) an interplay between pollution and climate change,” said Donald Uzarski, director of the CMU Institute for Great Lakes Research. "Climate change has drastically increased the occurrence and magnitude of extreme storm events causing excess runoff to enter the Great Lakes.”

Donald Uzarski, Director of the CMU Institute for Great Lakes Research

The runoff of pollutants plays a critical role in how invasive species, algal blooms, pollution and climate change are connected. According to Uzarski, invasive species are often able to take over an ecosystem because “nutrient pollution has artificially elevated primary productivity (algal blooms).”

Severe rainstorms and extreme precipitation events, like the rainstorm that affected Mount Pleasant this summer, are becoming more frequent. In late June, Central Michigan experienced severe flooding due to excessive rainfall that occurred during a concentrated amount of time – it rained very hard during a short amount of time and overwhelmed the infrastructure designed to handle stormwater.

On average, the city of Mount Pleasant receives about 32 in of precipitation a year. On June 22, it received 6.5 inches in less than 20 hours. On Aug. 2, President Donald Trump declared a state of disaster for Isabella, Midland, Gladwin and Bay counties.

“That is 20.3 percent of the annual precipitation in one day,” Uzarski said.

The storm resulted in $6.1 million in damage in the city of Mount Pleasant. In Isabella, Midland, Gladwin and Bay counties, the storm caused more than $100 million in damages throughout Mid-Michigan. That total includes $21 million to public property and at least $10-$15 million in agriculture losses.

Fifty-one buildings on Central Michigan University's campus were affected by the flooding. An estimate by the Facilities Management Administration placed the cost of on-campus damage between $7-10 million. Repairs were covered by the university's insurance.

While damage to private and public buildings can be cataloged and repaired, the damage done to the ecosystem of the Chippewa River is less easily measured.

“When that much water hits the landscape at once, it does not percolate into the water table but instead runs off into lakes and streams carrying massive amounts of pollution with it,” Uzarski said.

Streams and rivers then deliver the pollution that’s been introduced to the system into the Great Lakes. Much of the pollution that enters the streams are in the form of very soluble nitrogen. Increased levels of nitrogen can result in the excessive growth of algae and aquatic plants. When those organisms overtake the ecosystem they can block light to deeper water, effect oxygen levels and harm the food and habitat fish rely on.

While costal wetlands are still doing a good job of removing the added nitrogen, over 50 percent of the state’s wetlands have been developed over and filled. When Uzarski and his research team took samples to test the water quality, about 80 percent of the wetlands they sampled were nitrogen limited.

Uzarski and his team are working on a paper that would explain their findings. He believes that nitrogen is going to be just as much of a problem as other nutrient pollutants, such as phosphorus. The nitrogen content in the lakes is so high that a reactive-oxygen species toxic to even algae was produced.

“We experimentally added phosphorus, we did not see an algal bloom. When we added nitrogen we did,” Uzarski said. “That is, in these systems, it is the excess nitrogen causing algal blooms, not excess phosphorus yet the 2012 Water Quality Agreement does not even contain the word ‘nitrogen’ in it.”

Algal blooms can affect more than just fish habitat or recreation. In 2011, the city of Toledo issued a “Do Not Drink" advisory for more than 400,000 area residents served by Toledo Water. Chemical tests confirmed an increased, unsafe level an algal toxin in treated water.

Expect more flooding in Central Michigan

Martin Baxter a meteorology professor at CMU who researches precipitation systems, believes Mount Pleasant could experience a more significant impact every time a heavy rainstorm move into the area because the Chippewa River is already prone to flooding.

The tremendous amount of water vapor present in the atmosphere and an uplift caused by a front is likely to have caused the flooding seen in Mount Pleasant.

Martin Baxter, Professor of Meteorology at Central Michigan University

“With the changing climate we’re seeing warmer air masses that are able to hold more water vapor which can then potentially precipitate out into the heavy rainstorms we’re seeing,” Baxter said.

As the Earth’s surface and oceans warm, the amount of water vapor in the atmosphere increases as result of water evaporating from lakes, oceans and other reservoirs. Sea-surface temperatures today are the highest on record according to a State of The Climate report published in 2016 by the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) and the American Meteorological Society (AMS).

Dry places will become even drier, Baxter said, as warmer temps lead to less vegetation that can hold in water. Humid places will become more moist as they warm, as warmer air can hold more water vapor.

“There are models now that are capable of predicting where something like this will happen,” Baxter said. “The trouble is they aren't always accurate enough to give us the confidence to warn people of the potential impact of a storm like that.”

This year Michigan experienced one of its warmest Septembers on record. The state also experienced one of its wettest Octobers, which Baxter said isn’t a coincidence.

“There was a large warm and moist air mass caused by the evaporation over the Gulf (the Gulf of Mexico),” Baxter says. “There was no troughs or upper-level disturbances that could cause the air mass to lift and precipitate. You need to lift the air in order to get clouds to precipitate. In October two troughs were able to lift the air mass and cause rain.”

Climate changing agriculture

Warmer weather brings changes to more than just the distribution of water, it can affect the demographics of plants and animals. Joanne Dannenhoffer a botany professor at CMU, said as Michigan becomes warmer and experiences increased rainfall, she expects these changes to alter the composition of Michigan’s forests.

“Here in Mount Pleasant we live in a transition zone where the vegetation in the southern half of the state merges into the vegetation found in the northern half of the state,” Dannenhoffer says. “With warmer weather there might be a change in the migration of the transition zone, to say, somewhere farther north like Gaylord.”

According to the EPA populations of northern species such as paper birch, quaking aspen, balsam fir and black spruce may decline while oak, hickory and pine trees will increase.

"Plants have a general theme of adaptation, they've always been at the mercy of what happens in their environment," Dannenhoffer explained.

Dannenhoffer, who researches the kernel development of corn, says that increases in average temperatures could have both beneficial and harmful effects on farming in the state. The June flood ruined her research yield because crops, like corn, are intolerant to oversaturated soil caused by flooding.

“Corn doesn’t do well in a lot of rain,” Dannenhoffer said. “Flooding will affect the yield of corn and so will frequent hot days.”

Michigan’s lower peninsula, where most of its corn is grown, is likely to have five to 15 more hot days during the summer with temperatures above 95 degrees Fahrenheit. Though higher temperatures mean a longer growing season, it also increases risk for droughts can negatively impact the yield of corn and soybeans.

Joanne Dannenhoffer, Professor of Biology at Central Michigan University

Union Township farmer Jerry Neyer said his corn and soybean fields took the hardest hit from the flooding which occurred in June. Unlike his fields of hay, which have a larger root mass beneath them, the ground covering the soybeans and corns is easily washed away. This is problematic because nutrients essential to the growth of these crops is washed away.

"In July, things looked pretty good, but in August, especially towards the end of August, you could see the crop was starting to slow down and running out of energy," Neyer said. "It just didn’t finish out like it should – the corn was short, ears weren’t fully-developed at all in some cases."

The severity of climate impacts are still uncertain despite the advancement in climate and weather models.

Scientists know global average temperatures are rising, what they can't predict is how fast its going to warm up and what impacts that warming will have on Earth.

"I have kids and I hope to someday have grandkids," Kluver explained. "Some of these changes are going to happen no matter what we do and I want my kids and my grandkids to be okay. I'm a scientist and I look at the data and all of the numbers show what is happening and project what could potentially happen. I don't know how a responsible leader can ignore that."

Flooding damage to crops less than anticipated for Isabella County farmers

Mitchell Kukulka

Flooding caused by the June 23 thunderstorms represented one of the most costly agricultural disasters in Isabella County history. Updated damage estimates show between $10-$15 million in losses to local farmers.

Local farmers are still feeling the effects months later. A damage estimate released by the Isabella County Emergency Operations Center listed the cost to the area to be around $87 million, a number that included damage to agriculture, public property and private property. Agriculture made up $21 million of the initial estimate, though the total was raised to $28 million in the following weeks after deeper examinations were done.

Despite dire predictions, Michigan State University Extension educator Paul Gross said actual harm done to local crops will be lower than anticipated.

"There's impact, but certainly not what we thought we were going to get at the time (when) we were standing up to our ankles in water," Gross said.

Most crops have finished their harvesting season as of Nov. 30. Gross said current estimates for county-wide damages might end up being closer to $10-15 million, though final results won't come in until crop yields are totaled in January 2018.

Abe Pasch, president of the Isabella County Farm Bureau, said losses to his crops fell short of what he was anticipating during the summer.

"My preliminary thought was things were going to be really bad, but it wasn’t as bad as I thought it would be," Pasch said. "(In the summer) there were obviously some areas where the plants were gone. There were some other areas on the fringe of the flooding area where you didn’t know how well it was going to turn out."

Gross attributes the difference between the estimates and the current results to the fact that a flooded field can make farmers jump to negative conclusions, which doesn't always reflect reality.

"When you're standing there looking at a field that's underwater and asked to make a loss-prediction, compared to once you actually put the combine in the field at the end of the year, they're two completely different things," Gross said.

Pasch, who plants corn, soybeans, wheat and alfalfa, cites the unexpected "buoyancy" of crops for why the damages fell short of estimates.

He added the warmer than average months of September and October gave some local farmers the opportunity to replant crops they thought they had lost.

Gross said it was lucky for local agriculture that the flooding happened during a time of year with cooler temperatures and overcast skies.

When there's more sunlight, Gross said, plants that are underwater still go through photosynthesis. This would have meant the plants would have needed to draw more oxygen out of the air.

Farmers of dry beans and wheat felt some negative consequences resulting from the flood. More than half of dry bean crops were not planted as a direct result of the flood, Gross said. Wheat yields were also down by a margin of 12-15 less bushels than average.

Some corn crops were also affected. Union Township farmer Randy Recker lost as much as 30 acres of crops between soybeans and corn. Recker said rainfall in October disrupted crop production as much as the flooding had.

"We got about 13-14 inches (of rain) in June, but when you come back with almost 10 inches in the fall, that almost made everything harder than the flood did," Recker said.

Recker, who has been a farmer for around 45 years, said the June flooding ranks among the most damaging he has ever experienced, even higher than the massive flood that struck the area in September 1986.

"(During the 1986 flood), all the crops were there (in the fields), it was just a matter of trying to get (the crops) out," Recker said. "We finished up around January trying to get stuff out – damage-wise it probably didn’t do quite as much, it just made it a lot more miserable trying to do work."

Union Township dairy farmer Jerry Neyer said he lost between 10 to 20 percent of his corn crop as a direct result of the flooding.

"We probably lost $50,000 in our corn that we’ll either have to replace or go out and purchase if we fall short for feeding our cattle," Neyer said.

Despite the loss to corn, Neyer said his hay yields turned out higher than expected. He credits the higher performance of hay crops compared to corn to the bigger root mass hay crops have beneath them, which prevented soil from washing away along with fertilizer.

"The water didn’t wash (soil) away like it did where there was more exposed ground in the corn and soybean fields," Neyer said. "Even if it didn’t look like the corn had been washed away or damaged initially by the water, because we didn’t have the fertilizer that we put in that spring, our crops just ran out of food and energy to finish out the season. We lost our tonnage from that."

As of Nov. 21, the U.S. Department of Agriculture listed Isabella among 10 counties in Michigan that qualified as primary natural disaster areas due to damages caused by excessive rain occurring between May 4 and Aug. 4.

According to the USDA Farm Service Agency's website, farmers in eligible counties have eight months from the date of the declaration to apply for loans.

More information regarding eligibility can be found on the Farm Service Agency's website at www.fsa.usda.gov.

EDITORIAL: Global warming is an issue we must admit in order to repair

If you didn't believe in climate change before, 2017 was the year to start.

It was one of the most active hurricane seasons in recorded history. According to NASA, this October was the second warmest on record in the more than 130 years of weather record keeping. Here in Mount Pleasant, residents experienced the worst flooding since the 1980s.

Climate change is real. These are not isolated weather incidents. Each year, more and more evidence supports that our world is changing. Five pages of our paper today are dedicated to exploring these changes in global temperature, severe weather, Great Lakes pollution and Michigan's changing ecosystem.

Facts should form the basis of our opinions when it comes to important conversations on climate change and global warming. We are providing you with facts from academics who study this science. We hope our coverage inspires you to explore these topics even closer.

This is not a debate, however. We refuse to let baseless opinions be equivalent counter-arguments to established science and research.

While it would be difficult for one average person to make an impact on climate change, it will take a group effort to help stymie the ongoing efforts of global warming.

We understand it's not easy for college students to radically change their lifestyles, considering their time constraints and budgets. Several low cost and easy changes could be made to a person's life to account for their personal carbon-dioxide emissions.

The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), a nonprofit international environmental advocacy group, recommends the following for people looking to make a difference on a budget:

- Buy energy-efficient bulbs. While it might cost you a few extra cents now, energy-efficient bulbs help to use roughly 80 percent less energy than regular fluorescent bulbs.

- Reduce your water waste. Turn your faucets off when you brush your teeth, or spend a less time in the shower in the morning. According to the NRDC, "the EPA estimates that if just one out of every 100 American homes were retrofitted with water-efficient fixtures, about 100 million kilowatt-hours of electricity per year would be saved — avoiding 80,000 tons of global warming pollution."

- Take the bus. If you live close to or on campus, don't drive your car. Get up a few minutes early and take the bus to your midday class. Not only will this help to marginally cut down on carbon emissions, it'll save you the headache of trying to find a parking space.

As a newspaper, we deal in facts — not fiction. Scientists are releasing more research every day supporting not just the impact of climate change, but detailing the physical consequences global warming is having on Earth. Likewise, too many special interest groups and political hacks are actively trying to confuse the issue with misinformation and false-equivalency arguments.

The truth has become impossible to ignore: Climate change is real and must be addressed.

Don't leave this planet in worse shape than you found it. We can be one of the first generations to utilize the knowledge we have about global warming and make a difference.

The change starts with us. Let's change the world.