Native tuition waiver underfunded by state, universities pick up difference

Olivia Manitowabi-McCullough never dreamed of earning a college degree while growing up on the Hannahville Indian Tribe reservation in Michigan's Upper Peninsula. These days Manitowabi, a family studies major, plans to return to the Potawatomi Native American community after graduation to encourage other tribal members to pursue their dreams.

"To be able to go back to help your community is something you can do with an education," said Manitowabi, a junior at Central Michigan University.

Financial support she received from the Michigan Indian Tuition Waiver program made it possible for Manitowabi to attend CMU. The waiver program was created as part of a land exchange deal between state and federal lawmakers.

In recent years, the state legislators have underfunded the program by millions of dollars, leaving Michigan's state-funded universities to pick up the difference.

Without the program, Manitowabi doesn’t know how she would have been able to afford tuition and the costs associated with attending the university. She is upset that state legislators aren’t honoring the decades-old promise made to Native Americans.

"I would not have been able to afford or go to school without it," Manitowabi said. "There aren't too many Native Americans that go to college. There is a need."

The State continues to underfund

Michigan Speaker of the House, Kevin Cotter, R-Mount Pleasant, said the program has been under threat by legislators since he came to office in 2011. A CMU alumnus, Cotter said he is committed to protecting it.

"The tuition waiver program is a great program and an important part of the CMU community," Cotter said. "Many people were considering doing away with the waiver when I came into office, but I’m proud to say we saved it from the chopping block. We’ve actually increased funding for it in recent years."

Frank Cloutier, director of public relations for the Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe, said the state's lack of support for the program indicates a lack of concern for the needs of his people.

"I'm wondering why the state is underfunding its own program,” Cloutier said. “Where is the accountability?”

Last year, the state’s 15 public universities spent $4.7 million to subsidize tuition for Native American students. The state allocated only $3.8 million for the $8.5 million program, according to the Associated Press.

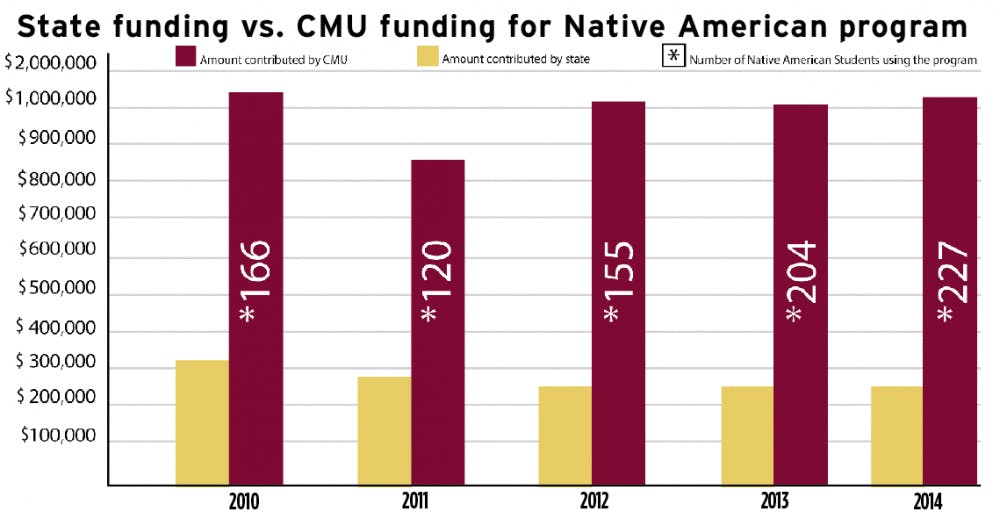

In the 2014 fiscal year, the state government appropriated $250,122 to CMU to pay for the tuition of 227 Native American students. Paying more than four times the state's contribution, CMU paid the balance of $1.2 million of the tuition cost.

At $302,706 in 2010, the state's contributions decreased by about $52,000 until 2012, where they have held the line during the past three years. CMU continued to pay more than $1 million each year since the decline ceased in 2012, and enrollment continued to grow from 155 in 2012 to 227 in 2014.

Next year, the Michigan Civil Rights Commission reports the state's estimated 2015 allocation to be just $343,799 to CMU, an increase of about $100,000 but still leaving CMU to pay more than $1 million.

To honor its relationship with the Native American community, Cloutier said the government should pay the full price of putting Native students through college.

"It's unsettling and unfair," Cloutier said. "CMU is already strapped for cash, and this puts Native Americans in a bad light. It was a deal between Michigan and the tribes.”

CMU President George Ross said the university is required to pay the difference left from state funding shortfalls. He said the lack of funding from the state for the program is just part of a continued trend of reductions in state aid for universities.

"I think the state should pay the whole thing," Ross said. "I think it's a good program, but it's falling on us mostly.”

Ross was firm in his commitment to support the Native American program.

"It's a wonderful program that allows hundreds of students to get an education that probably wouldn't be able to get one," he said. "But, it's a state program. I think they should pay all of it."

Decades-old deal

Native Americans were first given free tuition in a 1934 agreement between then Michigan Gov. William Comstock and the Federal Government.

According to documents from the Michigan Legislative Service Bureau, Comstock petitioned the U.S. Government to turn over ownership of the land and buildings of the Michigan Indian Industrial Boarding School in Mount Pleasant. The governor intended to turn the facility originally intended to educate and "westernize" Native children into a school for the developmentally disabled.

The federal government agreed to surrender the land if Comstock agreed to provide free education to Native Americans. To be eligible in the waiver program, students must live in Michigan for one year, attend a public university and be a member of a federally-recognized tribe. They must also posses a Native American blood quantum of one quarter.

A person's blood quantum is the percentage of their ancestors who are documented as full-blood Indians.

Despite concerns about the state honoring the agreement, Director of Native American programs Colleen Green said the university has no plans to turn away students. The mother of three utilized the program herself after working for minimum wage until she was 28.

"They signed the agreement, so they should pick up the tab," Green said. "I do not think it's fair. It was a contract that was made with the tribal nations and the government."

The waiver program has already proved successful in connecting Native Americans with college degrees. Those communities benefit from having educated, motivated leaders, Green said.

“People go back to tribal communities from school to get higher positions and benefit everybody. It has gone to people in the community who have been successful,” she said. "I wouldn't be here without the tuition waiver.”

The 80-year-old agreement should be honored, Cloutier said, as a contract between the State of Michigan and its Native tribes. The implications of the agreement go far beyond the financial or social barriers of Native Americans.

"There is a promise that is not being upheld," Cloutier said. “We were promised higher education. Do your job, or give us our treaty rights back."