Breaking her silence: Graduate student Rachel Wilson shares her story of sexual assault, seeking justice

“Do you want to have sex?”

She stared at the man standing near her. The woman, a recent transfer to Central Michigan University, was wearing his clothes. She laid on his bed, in his room, disoriented. She began to suspect that she had been drugged.

“I just threw up and blacked out,” she replied. She remembers not understanding why he was trying to initiate sex after he had watched her vomit.

He moved closer to the bed. The 22-year-old man, a familiar student leader on campus, stood over her. She said he told her that it didn’t matter to him that she had just been sick and that she had passed out.

It began.

She remembers him kissing her sweaty neck and face. She told police she could taste bitter vomit in the back of her throat as he forced his mouth on top of hers. She said she remembers him pulling her back to him each time she pulled away.

As he laid on top of her, her body went still. She later told officers she didn’t know what to do as she became increasingly scared of him. The man on her weighed almost 250 pounds and stood six feet tall.

She froze.

Meet Rachel Wilson

A first-year graduate student at Central Michigan University, Rachel Wilson is from Hudsonville, Michigan.

This is her story.

Being a college student is the one thing Wilson said she always felt she was good at. She earned a 4.0 GPA. She loves learning, going to class and studying. A Grand Valley State University transfer, her plan was to pursue a double major in psychology and neuroscience. By fall 2018, she planned to be taking graduate courses at CMU.

Her experience that night changed everything. Wilson said she is no longer seeking justice, but she is trying to promote understanding – about the challenges survivors face when dealing with law enforcement and about the aftermath, which she said can violate survivors just as much as an attack.

The assault

“Suck my dick.” That’s what the man said to her, Wilson told police, after he removed his pants and underwear.

He put his penis in front of her face.

No, Wilson said.

“Don’t you understand how this works?” he asked her, according to the police report about that evening. “Why did you even come here?”

She had already told him no several times, Wilson said, and she felt physically weak. Later Wilson told police officers that she opened her mouth and briefly performed oral sex on him.

He took off her pants and underwear at the same time, Wilson said. It now seemed imminent. Wilson told police, university investigators and court officials that she never consented to sex with him – and that she was afraid. She wasn’t on birth control. Her mind raced – how could she protect herself from an unwanted pregnancy or a sexually transmitted disease?

“Condom,” Wilson gasped.

He insisted he was “good at pulling out.” He argued. He left briefly to get a condom from a roommate. She laid still as he pushed himself inside of her. Wilson stared at the ceiling. She felt his hands gripping her thighs, pinning her to the mattress. The Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner who treated Wilson the following day documented the hand-shaped bruises on the inside of her thighs. She wished for it end.

He finished. She felt numb, trying to comprehend how this had happened to her.

As she lay there her adrenaline took over. It helped her regain some of her balance and strength. She franticly searched for her clothes.

It was about 3 a.m., and Wilson had no idea where she was.

She had no idea how she was going to get home.

“Where are you going?” he asked as he watched her from the bed.

She mumbled something about having an 8 a.m. class.

“I couldn’t think of anything else,” Wilson recalled, “but to get out of there as fast as I could.”

Earlier that day

Wilson spent hours at the library on Aug. 31, 2016. She was writing her personal statement for her graduate school application. Tired and anxious, she felt she needed to unwind. She wanted to take her mind off of school for just a couple of hours.

Wilson had met a guy, and she wanted to get to know him better. He was friendly and funny. She texted him and asked if he’d like to go out and “grab a beer.”

He replied yes. Wilson was excited. They agreed to meet at The Cabin.

It was a busy Wednesday evening – The Cabin’s popular $2 Pitcher Night – and it was packed with students. Wilson arrived at about 10 p.m.

He was late.

Wilson was excited to meet her new friend, so she decided to order a beer while she waited for him. The music blasted as she worked her way through the crowd to the bar. A bartender took her order and handed her a glass of beer.

Finally, he arrived — with another woman and other friends in tow.

She was disappointed. It now seemed she wouldn’t get to spend the night getting to know him. Nonetheless, she was determined to have a good night. An 8 a.m. Organic Chemistry lab would prevent her from staying out too late.

Wilson sipped her first beer as she and her friend chatted, yelling to be heard over the music.

Not long after he arrived, the man ran into a friend at the bar. He enthusiastically introduced Wilson to his tall, personable friend who she later described as talkative, outgoing and a “life of the party” type of person.

“Everyone at the bar seemed to know who he was,” Wilson said. “He was talking to more people than I even know.”

Wilson and the friend of a friend made small talk. After a few minutes he left to talk to other people.

“You should get to know him, he’s a really nice guy,” said the man who Wilson intended to meet that night. His comment annoyed and confused her. Was he trying to set her up with his friend?

She ordered a second beer and sat down at a table with a group of people. Wilson recalls having a nice conversation with the energetic, charming person she had been introduced to. She thought the beer tasted bad, so she drank less than half of it before ignoring it on the table.

When she stepped away from the table, and began walking to the bathroom, Wilson began to feel “weird.”

“I remember thinking everything feels strange; a sort of out-of-body experience,” Wilson said. “At the same time, my body felt overly relaxed.”

Suddenly, Wilson felt she was not acting like herself. Wilson describes herself as a shy, reserved person. That night she recalls being a “chatterbox.” She initiated long conversations with girls in the bathroom she had never met. When she returned to the table, she talked loudly with everyone — especially with the man she’d just met. Weeks later when questioned by CMU’s Office of Civil Rights and Institutional Equity investigators, a witness said he thought Wilson was drunk that night because “she was being loud.”

“I had absolutely no inhibition. I had no little (voice) inside of me saying, ‘You shouldn’t do this, it’s getting late. You have lab in the morning. You drove your car here, Rachel,’” Wilson said.

Based on their interviews with her, police suspect Wilson was drugged that night. Unfortunately, they would never be able to prove it. The SANE nurse who administered Wilson’s rape kit the following day told her that any date rape drug would no longer be in her system, especially because Wilson had vomited several times.

The nurse did not take any blood or urine samples for evidence.

Wilson’s new talkative friend stayed by her side all evening. A cab was waiting outside, the man told Wilson.

Together they got up from the table and walked out of The Cabin.

At his house

“Get up. You’re going to get us in trouble,” Wilson recalls him saying to her as she laid in the grass outside of his house. Why would we get in trouble, she thought to herself. Wilson had stumbled out of the cab and according to the OCRIE report told investigators that “she was unable to get up and everything was really spinning.”

She leaned on him as he helped her walk to the house. They entered through the back door of the house and went into his bedroom.

Something was wrong. Wilson felt she was about to be sick.

He handed her a trashcan and she “vomited so violently it hurt,” Wilson told OCRIE.

When it didn’t appear that she was going to stop throwing up, he became concerned that “something medical” was going on with Wilson he later told OCRIE. He summoned the man who introduced him to Wilson earlier that night, and the woman who was with him, to the house. The woman helped Wilson change into clean clothes. Wilson passed out.

The men sat together in a nearby room, according to the OCRIE report, talking and drinking “a small amount of scotch, neat.” After about 60 minutes the man and woman left.

Wilson was now alone with a man she had met only a few hours before, in his apartment, unconscious.

Trying to understand what happened

“I think I was raped.”

During her appointment at the Counseling Center the next morning Wilson broke down. The counselor advised her to go to McLaren Central Michigan Hospital. She was examined by the SANE nurse and met with a Mount Pleasant Police Department officer.

On Sept. 1, 2016 at 10:32 p.m., he texted her.

Him: I was really worried this morning...

Him: I’m sorry I didn’t walk you home. That was really rude of me

Him: U there? I’m confused

Her: I’m here.

Him: Did (the mutual friend) give you my number? Why didn’t you text me

Her: Yea. Because I didn’t want to :/ what do u want me to say

Him: Well I guess I’m just confused

Her: About what?

Him: Are you mad?

Her: Yeah I am

Him: Wait really

Her: Yea

Him: At me?

Her: Yea

Him: Why? Can I call you?

Her: Did someone put something in my drink?

Him: Seriously?

Her: U realize I drank two beers

Him: Can I call you?

Him: Listen, I’m not that guy

Him: Please

Her: Really? Because you really insisted on sex after I got done puking my brains out

Him: Woah

Him: No that’s not quite what happened

Him: Please can we talk on the phone

LATER THAT DAY

Him: I’m so sorry

Her: I don’t know what to do

Him: I honestly thought you were serious when you said you want to have sex

Him: I’m so sorry

Him: Please don’t

Him: What can I do?

Him: I wanted to like hang out and get to know you

Her: I wasn’t u were just so persistent and I thought u knew that I said I didn’t feel like it when I said it the first time

Him: I don’t remember that at all

Him: I’m so sorry

Her: Don’t panic ok?

Him: I just remember you waking up and me asking you saying we could if I found a condom

Him: This could ruin my life

Him: I’m like having a panic attack

Him: I’m so sorry

In the days that followed, they continued to communicate. They met up in the Down Under Café to speak face to face.

She was confused and conflicted. Wilson thought she would be better off if she forgot about that evening and forgave him. She felt bad for him – he cried and told her he was “not raised that way.” He told her that his mother had recently died. He told her in a text message that an adviser was going to help him connect with substance abuse counseling.

He has sisters, he told her.

8:33 p.m., Sept. 2, 2016

Her: What’s going on?

Him: I’m trying to be present with my friends but I just keep thinking about every possible what if running through my mind every time I’ve been with a girl in the last year and just like picking apart every moment to see if I might have been too drunk to hear someone’s hesitancy even if they ultimately said yes and like just running through every possible scenario and how my family would feel if I got arrested and like ppl I might have hurt and not even known it. I’m trying so hard to trust you and my own memory but now I’m second guessing everything and I’ve been just totally out of my mind all day.

LATER

Him: Like what if there is someone else? If they find out about your kit that might sent someone over the edge I don’t even know about. I could still be hurting ppl even if I get help

OCRIE investigation

On Oct. 19, 2016, Wilson informed the OCRIE office that she wanted to move forward with an investigation into that evening under the university’s sexual misconduct policy. The OCRIE investigation lasted the rest of the fall 2016 semester.

Wilson met with representatives of the office several times.

To begin the investigation, she first had to tell her story of the assault, in explicit detail, to OCRIE representatives including Katherine Lasher, executive director and Title IX coordinator. She provided them with text messages which, she explained, showed evidence of his guilt.

He also met with OCRIE representatives and presented his interpretation of what happened that night. Throughout the investigation, he maintained that he and Wilson engaged in consensual sex. He told investigators he asked her several times if she wanted to have sex and she answered “yes” each time, if he used a condom.

He said he was innocent.

The investigation concluded on Dec. 20, 2016.

OCRIE found in Wilson’s favor and determined that the man had “engaged in sexual assault” according to its report. The office found that he engaged in sexual contact with a person who “was incapacitated on the evening of Aug. 31.” She “therefore was incapable of consenting to sexual activity,” the report states. OCRIE recommended that he be “suspended from the university for an appropriate amount of time” and that he have no further contact with Wilson.

He did not return to Mount Pleasant the following semester. The Office of Student Conduct expelled him. Student Government Association posted on social media that the campus leader resigned “due to personal reasons and opportunities.”

Wilson didn’t return to CMU either.

Depressed and disillusioned, she moved back home seeking comfort from her family in Hudsonville. She spent the next few months working, spending time with her family and trying her best to move on from what happened to her that evening.

In April 2017, Wilson received a phone call from a detective, informing her that the results from her rape kit had come in. DNA had been found in three areas on her body—on her cervix, her stomach and in her anus.

Up until that point, she wasn’t convinced she should press charges against him. She felt she already endured so much trauma. When she received the rape kit results, she decided to press charges and move forward with a criminal investigation against the man who she believed sexually assaulted her.

Police investigation

Wilson traveled to Mount Pleasant to give detectives a formal statement and to confirm she wanted to press charges. During the following months, she received frequent calls from Mount Pleasant detectives updating her on the case. Detectives filed a warrant to swab her attacker’s mouth and collected the sample in November 2017.

Wilson’s complaint was sent to the Isabella County Prosecutor’s Office in August 2017.

Prosecuting attorney Risa Hunt-Scully told Wilson she believed her. She also told Wilson that she felt they had a strong case. Wilson’s case was assigned to assistant prosecutor Larry King, who is now running for prosecuting attorney in the Nov. 6 general election. Wilson said King also told her that he thought they had a good, strong case.

On Jan. 9, 2017, Ian Elliott of Cheboygan was arrested and arraigned on three charges: two counts of sexual misconduct in the third degree and assault with attempt to penetrate. Wilson was set to face Elliott, the former Student Government Association president, in Isabella County District Court. He posted bail immediately.

Elliott was contacted for comment for this story. He declined to be interviewed.

A preliminary hearing was scheduled for Feb. 1, 2018. The purpose of a preliminary hearing is so the court can decide if there is enough probable cause to believe that a crime was committed. The court can weigh evidence and testimony of witnesses to screen out cases that cannot be later proven at trial.

Wilson took the stand and was questioned by defense attorney Joseph Barberi for more than two hours. Because no blood or urine samples were taken from Wilson at McLaren, Barberi stated that Wilson could have taken drugs prior to the incident, causing her to be incapacitated that night.

Judge Eric Janes bound the case over to circuit court.

A jury trial was scheduled for May 7, 2018.

Wilson’s case would never make it to trial.

Not strong enough

Interim Prosecutor Robert Holmes had been appointed to the position after Hunt-Scully left office to take a job in the Michigan Attorney General’s Office. Three weeks before Wilson’s case went to trial, assistant prosecutor King informed her that the case was being dismissed.

Holmes, who had never met her, was worried that Wilson was “not strong enough” to withstand a jury trial, she said.

Wilson demanded to meet with Holmes and scheduled a May 11 meeting in his office. When she arrived, Wilson was accompanied by Det. Chuck Morrison, who worked on her case, and a victim’s advocate who did not speak to Wilson during the meeting.

Holmes immediately told her he dismissed the case because he felt there wasn’t enough evidence, Wilson said. She “could have run away,” Holmes told Wilson as he continued his reasoning for dismissing the case. Wilson said Holmes dismissed the hand-shaped bruises on her thighs, saying they were only evidence her thighs “were being used as leverage” during sex.

The acting prosecutor also told her that King solicited the advice of Steve Thompson, the CEO of No Zebras, emeritus CMU faculty and former Sexual Aggression Service director. During his comments, Wilson said that Holmes implied that Thompson, a nationally-recognized expert, didn’t think the case was strong enough.

An email from Thompson to King obtained by Central Michigan Life shows a different story. Thompson sent a blistering rebuke after he learned that his name was used to try to convince Wilson that her case is too weak to take to trial.

“... It is a rare sexual assault case that is not difficult. The case was dropped prior to any substantive discussions with me. Had I been consulted I would have been able to address how you could overcome some of these difficulties,” Thompson wrote. “Not only was Holmes not telling the truth, it was unprofessional behavior attempting to make me the one responsible for your office not moving forward with the case. Because of the actions of your office a young woman and probably a few others at that meeting question who I am. This is not acceptable.

“I have attempted to speak with Holmes but my call has not been returned. I want to know what will be done to attempt to make this situation right and the survivor be given the truth. That truth seems to be the prosecutor’s office has to be assured of a win otherwise it does not either have the legal skills or desire to take on a difficult case.”

Holmes was contacted for comment for this story.

He declined to be interviewed, but did send an email response: “The facts surrounding her involvement with Mr. Elliott were unfortunate. Those facts however, when viewed in a light of what is necessary to obtain a conviction beyond a reasonable doubt, were simply insufficient,” Holmes wrote. “Ms. Wilson disagrees with that assessment and is angry with my decision to dismiss the case against Mr. Elliott, as a result of the insufficiency of the evidence.

“The ill-advised decision to issue criminal charges in this matter by a resigning prosecutor, coupled with the inexperience and lack of reference of the assigned Assistant Prosecutor, left me with the difficult decision of ending a flawed case before any more unintended consequences were realized.”

Holmes was defeated in the Aug. 6 primary election race for Republican candidate for prosecuting attorney. Republican David Barberi will face King on the Nov. 6 ballot.

Moving forward as a survivor

Wilson will never have her day in court. She officially lost her chance to pursue a legal case against Elliott on Sept. 1, 2018, when the two-year civil statute of limitations passed.

Wilson spent the last two years fighting for closure and getting people to understand what she went through by reliving her story — telling it over and over again. Her experience with the Isabella County prosecuting attorney’s office, Wilson said, felt like being violated a second time.

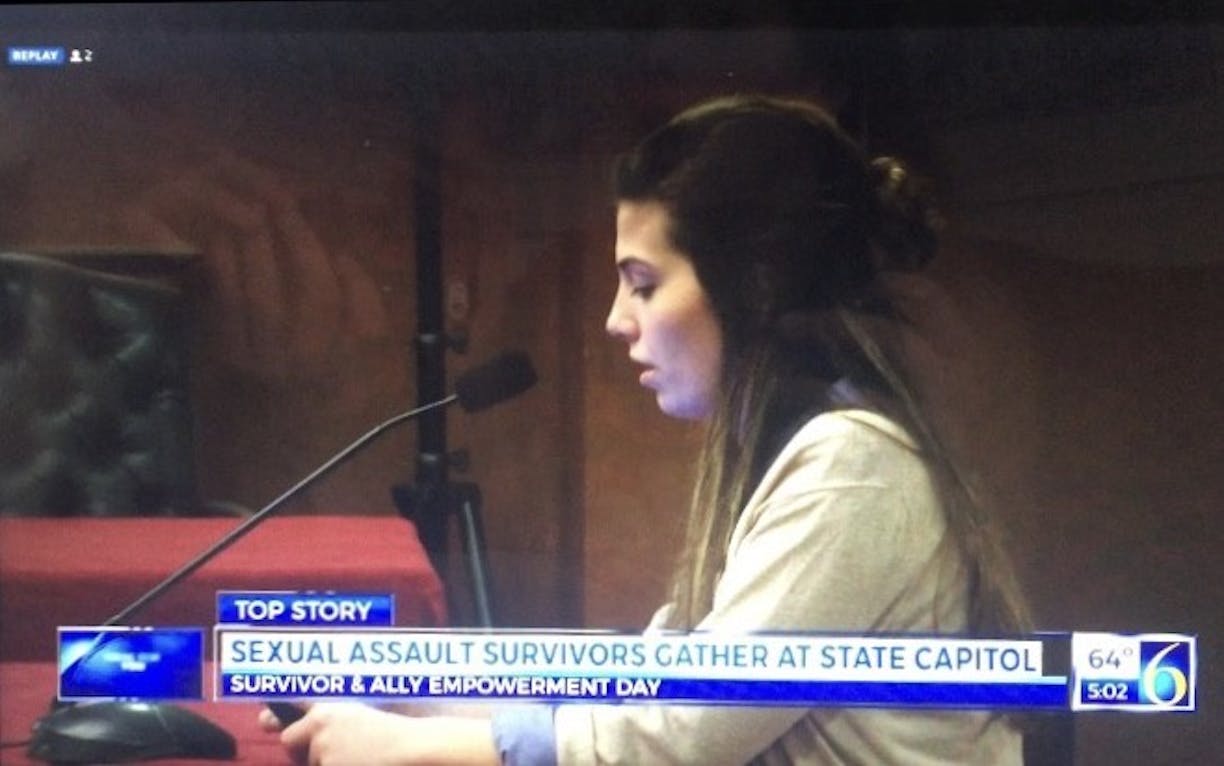

Rachel Wilson spoke on April 26 in Lansing at the Capitol Building. Courtesy Photo

“An entire county of adult professionals who are trained in serving justice to people are turning their back on me and invalidating everything that I brought to them. I felt like I couldn’t trust or turn to anyone,” Wilson said.

Despite all of it, Wilson wants you to know that she is going to be OK. She won’t ever be the same, but she has found her voice. This experience taught her just how far her voice can carry.

On April 26, she shared her story with hundreds of people during the “Consent Forum” at Survivor and Ally Empowerment Day in Lansing. On Oct. 9, Wilson attended the SANE board meeting to speak about the need for more thorough and regulated sanctions for rape kit examinations.

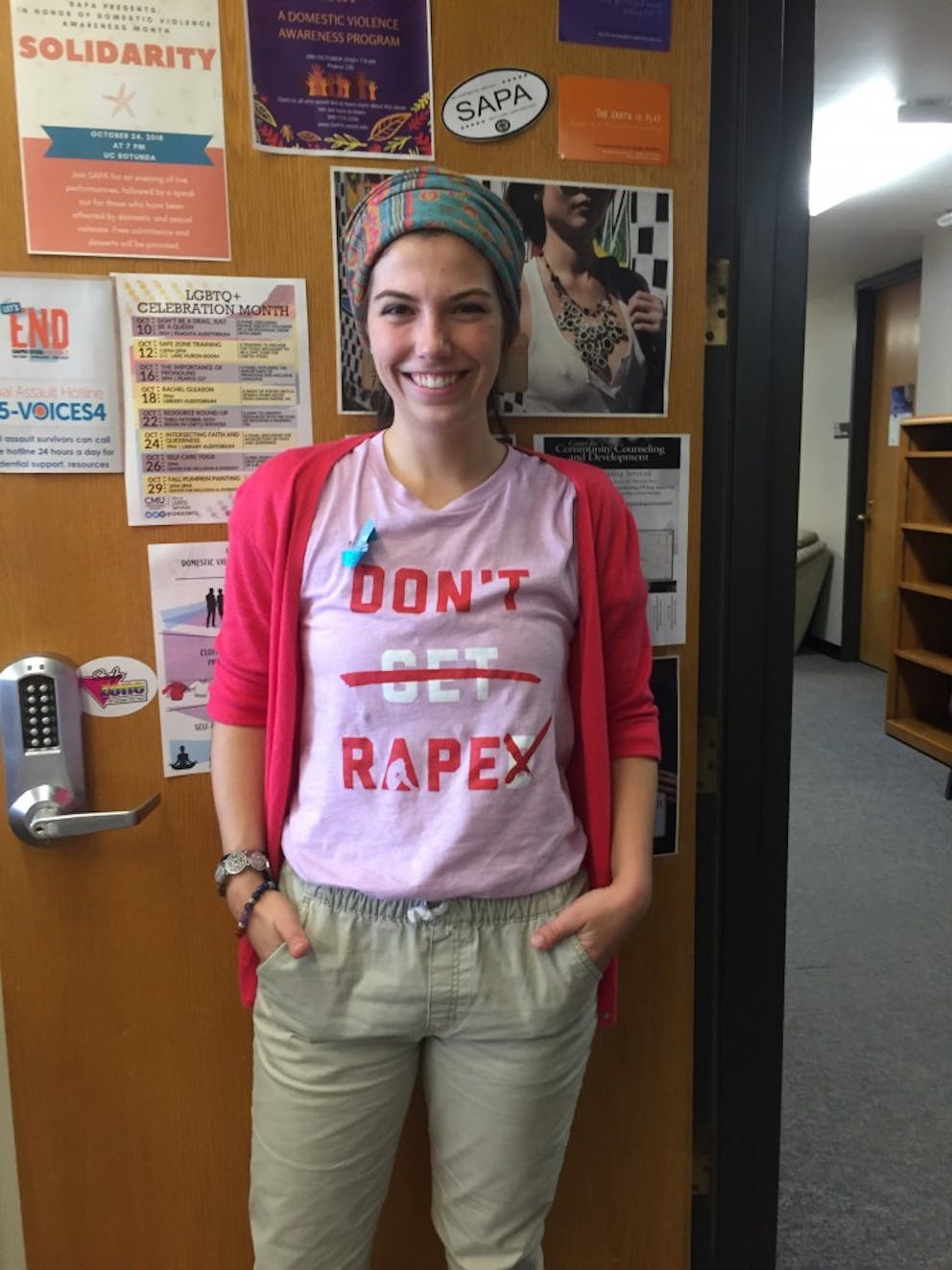

Rachel Wilson before speaking at the SANE board meeting on Oct. 9 Courtesy Photo

After she completes her graduate program in 2020, Wilson will begin her career as a counselor. She wants to work with victims of trauma so she can help them through the hardest times of their lives.

Wilson has no doubt that she will be fighting for, and alongside, sexual assault survivors for the rest of her life. She is passionate about being a sexual assault survivor advocate and educating people about the many ways others try to impede these investigations.

Wilson is positive that by making her voice heard, and telling her story, that she will be part of the movement to end campus rape culture.

She is not a victim. She is a survivor.

EDITOR'S NOTE: An earlier version of this story misstated that Judge Paul H. Chamberlain bound the case over to circuit court.