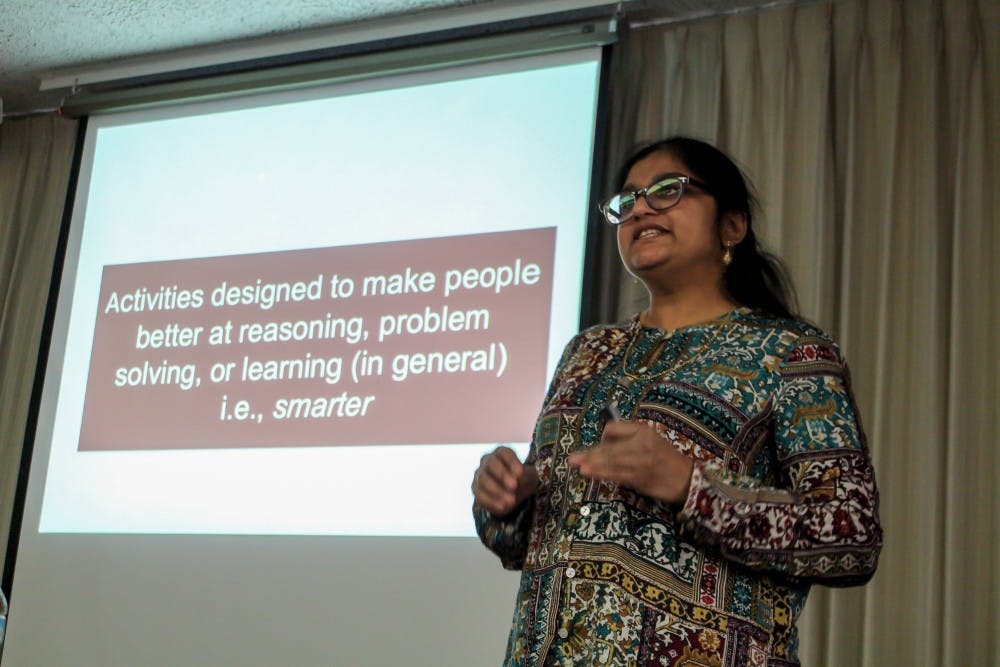

University of Michigan psychology professor discusses 'brain training' science

A University of Michigan psychology professor presented her research on children learning with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and the science of "brain training."

Priti Shah showed students the background behind brain training science through "How to Play 20 Questions with Nature and Lose" on March 19 in the Bovee University Center. The presentation gave the history of the field and how it is changing today.

Shah, who teaches in the School of Education at U-of-M, described brain training as “cognitive training that often targets attention, working memory, or most broadly, executive functions.”

The history of brain training, Shah said, tends to repeat itself. From the start of the industry until modern day, researchers have been going back and forth on the use of these tests. Shah added that history also includes a lot of misinformation.

Brain training as a concept was first popularized in books written by Catherine Aiken, a pioneer in the field, Shah said.

Aiken started working memory brain training at her school where she taught people how to improve memory and subitizing training. Shah described it as “immediately recognizing the number of objects without counting them.”

Karl Dallenbach, a different scientist, chose to study children. His 17-week study showed “practically certain” improvement on children in the test, Shah said.

Shah’s own study chose to focus on children as well, specifically those with ADHD.

The study set out to find a medium to test children in a more friendly way. Shah and others in her study used a video game that had children memorize the locations of frogs.

The group's study started by giving them a pre-test, then 20 15-minute sessions and a three month follow-up test.

“In the field that I am in we have a tendency to do a lot of similar research," said Florida graduate student Basha Libman. "They are much in the same family as this one.”

Shah’s research showed that children slowly improved at most of the games. The kids taking the test also had a long term improvement over those who did not take the test.

“In my lab we study memory so I thought it was interesting that just by doing these types of training tests you can improve people’s working memory,” said Indiana graduate student Monica Hamaker.

While not all kids improved, Shah speculated that children who enjoyed the game became better, while those who did not like the game did not try to improve. Another possibility is that some children are just better at learning.

Shah also concluded that brain training had more improvements when spaced out over a long period of time. The bottom line when it comes to brain training is a simple one: no one knows for certain, and people shouldn’t claim to.

“Nothing is fully conclusive,” Shah said. "No press release should say that it does or it doesn’t.”

Mark Reilly, a professor of psychology at CMU, said he was pleased with Shah's presentation.

“I like the thoughtful approach to an area that I think there is not enough of," he said. "A lot of times this topic is sold as snake oil.”